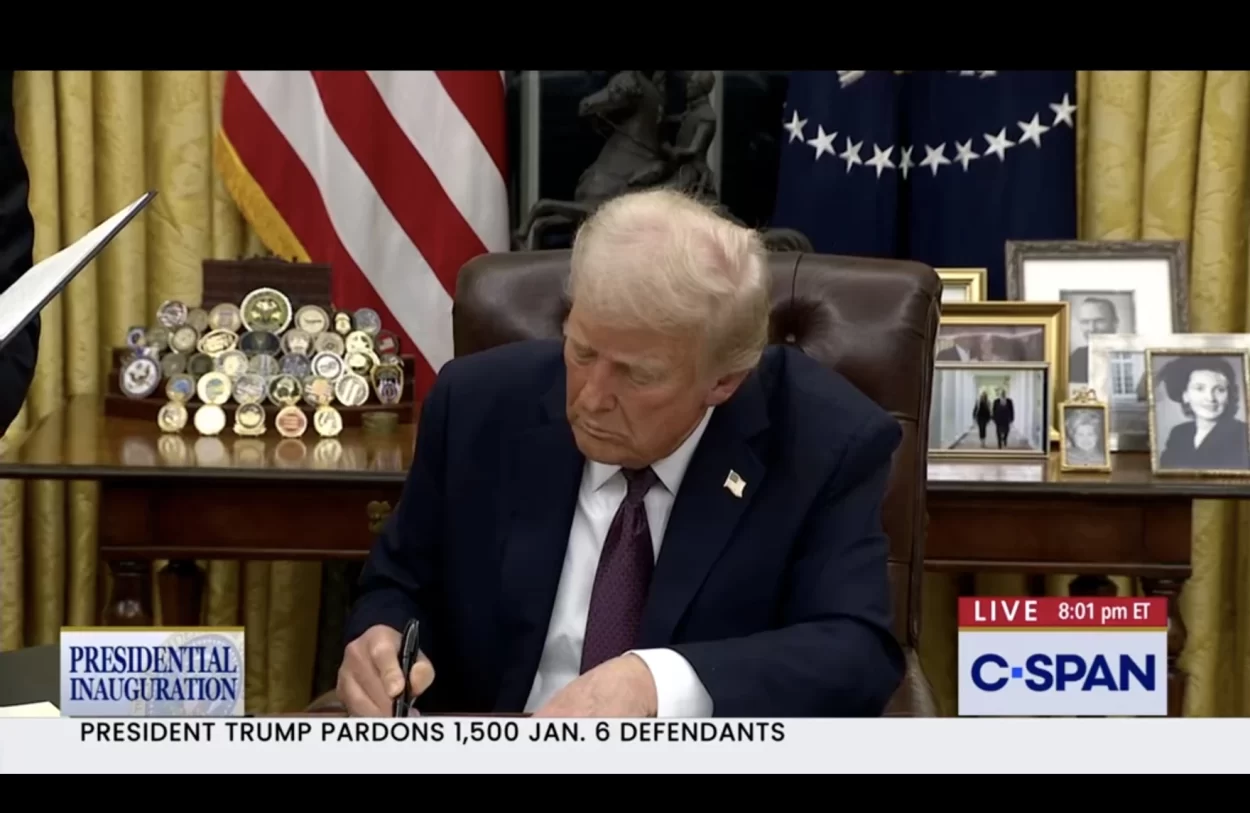

In the first two days of his new term, President Donald Trump signed more than 200 executive orders. One was aimed at accessing more natural resources in Alaska. It attempts to roll back protections on over 9 million acres of Tongass National Forest, potentially opening them up for logging.

Trump’s executive order is titled “Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential.” The order alleges that restrictions on mining, logging, oil drilling and other resource extraction on Alaska’s federally protected lands is “an assault on Alaska’s sovereignty and its ability to responsibly develop these resources for the benefit of the Nation.”

The Tongass is the world’s largest remaining temperate rainforest. The Trump administration is seeking to rescind the Roadless Rule, which prohibits road construction and timber harvest on over 58 million acres of national forests across the country.

The Jan. 21 order won’t have any immediate effect on the ground. Normally, an executive order like this would kick off a lengthy public process with the U.S. Forest Service and its parent agency, the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The Juneau-based Southeast Alaska Conservation Council has been fighting to keep most of the Tongass roadless for decades. The conservation council director Maggie Rabb said it’s hard to predict what this administration will do next.

“This president has proven to be unusual sometimes, and so we’re not sure,” she said. “It is possible they could just try to remove it and skip the public process.”

The Tongass covers most of Southeast Alaska and is the largest national forest in the country. The conservation council was formed in 1970 specifically to combat wide-scale, industrial old growth logging in the forest.

During his first term, Trump took action to exempt Alaska from the Roadless Rule, only to be reinstated by the Biden administration. Rabb said the rule has been rolled back and rolled forward by various presidents pretty much since its inception – but not without a fight.

“If they do remove the Roadless Rule, it would start – it could start new litigation that we would join to put the Roadless Rule back in place, and then we would be suing against the Forest Service,” she said.

The conservation council has been involved in litigation around the Roadless Rule off and on, but as the presidential administrations change, so do their legal allies.

“The parties on our side change whether we’re with or against the federal government,” said Rabb.

During the Biden administration, the conservation council was suing the State of Alaska on behalf of the federal government to support its protections of the Tongass. That case is now on hold.

It’s possible the current administration could completely remove the Roadless Rule and begin fielding proposals for new logging roads through the forest.

“How quickly that happens is very much a question, because logging has not proven to be that profitable for quite some time,” said Rabb. “Why would you push to further grow a logging industry that’s costing the taxpayers money and supports less than 1% of our regional economy?”

Rabb referenced a 2020 report from nonpartisan federal watchdog group Taxpayers for Common Sense that found that the federal government was actually losing money on timber sales in the Tongass.

“These sales have consistently generated less revenue than the USFS spends to administer them, resulting in large net losses for U.S. taxpayers,” the report said, adding that taxpayers were subsidizing the region’s logging industry to the tune of $1.7 billion over the last 40 years.

Rabb said that the conservation council is not anti-logging. There is still active logging in the Tongass. For Rabb, the Roadless Rule has been an effective tool to protect old growth without actually ending logging.

“The push to roll back the Roadless Rule has very little to do with on-the-ground realities in Southeast Alaska or market demand, and it’s very much about external agendas that are disconnected from our region,” she said.

According to Rabb, the removal of the Roadless Rule has been a conservative talking point for years and was outlined in Project 2025, an infamous conservative policy roadmap for the Trump administration aimed at reshaping the federal government. Trump has at various times embraced the document and its architects and distanced himself from its ideological extremes.

“If you actually look at the language there, one of the reasons they articulate for getting rid of the Roadless Rule is that it ‘forces residents to rely heavily on a subsidized ferry system,’” Rabb said, referencing the Alaska Marine Highway System. “But I would love to have someone explain to us how removing the Roadless Rule would allow you to drive from Ketchikan to Sitka. It’s just preposterous. It has very little to do with our realities.”

Keith Landers has operated a small sawmill on Prince of Wales Island for the last 30 years. If you’ve ever flown to Alaska, you’ve probably passed beneath a wooden, mushroom-like sculpture in the N Concourse of Seattle-Tacoma Airport. Landers brags that his mill supplied the wood for that sculpture, as well as the cedar-planked ceiling above passengers heads.

He doesn’t think more logging in the Tongass is a bad thing.

“We need to be truthful about our forest,” Landers said. “This is a big forest. It grows over a billion board feet a year. No one’s going to clearcut the whole thing.”

Landers said he hasn’t had a winning bid for Tongass timber in two years because larger competitors outbid small mills for the limited inventory. Most of that wood, he said, doesn’t stay in Alaska.

“I’m really looking for an honest program, something that supports stuff besides outside influence,” Landers said. “Over the 30 years I’ve been here, nothing has been done. I have never felt like I have been supported by anybody.”

Landers said he’s glad for anything that would open more timber for his mill, but only if it prioritizes Alaskan operations and supplies locals first. As opposed to “more large corporations buying up the Tongass and shipping the lumber overseas.”

“I’ll be honest with you, under the first Trump administration, he rolled back the Roadless (Rule) and never did a darn thing,” Landers said. “We have to have a serious conversation about what we want to do with our forest and to create some jobs here because their word is worthless. It’s worthless. It’s not for local people.”

Landers hopes the new Trump administration can guarantee reasonably priced, sustainable Tongass lumber, without environmental groups like the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council taking them to court over each timber sale. But he’s not optimistic. For Landers, the rules changing every four years makes it hard to run his small business.

“We just can’t continue to have timber for four years and then under the next administration, have no timber at all. It just doesn’t work real well,” Landers said, adding that what the Tongass needs is a balanced timber program that both political parties can get on board with.

“That’s what I would tell Mr. Trump. I would say, ‘We got to have a forest plan that works and that’s guaranteed for people to invest,’” Landers said. He added that it’s a waste to spend millions of dollars on timber sales and logging infrastructure, “And then turn around and tear it down in four years. Don’t bother us.”

Landers recalled that when he first got into the logging business, there were “probably around 30 small mills” in Thorne Bay. Now, his mill is one of three. He said his children will inherit the mill when he retires but something has to change.

“This will continue to go on,” he said about the mill. “But I’m not putting my family through what I went through over the years. It’s been nothing but a dogfight with the environmental groups.”

Joel Jackson is the president of the Organized Village of Kake, an Alaska Native tribe located on Kupreanof Island in the heart of the Tongass. He’s been supporting the Roadless Rule since it was enacted, because he says the old growth trees it protects are essential for preserving their way of life.

“It took thousands of years to become what it is today,” he said. “The canopy of the old growth trees are spaced in such a way that it allows growth underneath the trees, and that’s where we collect our medicines and our berries and everything else that’s there.”

Jackson respects anyone trying to make a living – he worked in industrial logging himself during its heyday decades ago. But he’s also seen huge swaths of clearcut forest change the landscape.

“I’m not against anybody working, but, gosh, we got to be able to manage our resources better than what we’ve done in the past,” Jackson said.

“There is broad, sweeping support of keeping the Roadless Rule on the Tongass. And so I think our job is to bring those voices together again and show that we can have a healthy Southeast Alaska with the Roadless Rule here in place, and that it is an important tool that we don’t want to throw out,” said Rabb.

Trump hasn’t made his picks for who will lead the USDA or the Forest Service so he hasn’t formally staffed the agencies or roles that he’s giving direction to.

USDA spokesman Wade Muehlhof said in an email that they are in the process of reviewing Trump’s executive orders. Afterwards, he wrote, they’ll tell agencies how to implement them as soon as possible.