Rose Ann Bruce came to Alaska from the Philippines about a year and a half ago. Now she’s a junior at Ketchikan High School — and she is working on her English.

“As you can tell, my grammar is, like, not very good. But I’m trying because that’s not my first language,” she said.

Her first language is Tagalog. She speaks English carefully. Sometimes, when she’s saying something important, she’ll write it out in her phone’s Notes app and then read it.

Bruce said her grades are good, but assignments can be harder when you don’t know all of the words in the instructions. Plus, she feels like her peers and teachers have certain expectations.

“Like, ‘Oh, you’re in the U.S. You should know how to write an essay. You should know how to answer this,’” Bruce said. “But what if you can’t? What if you’re just learning?”

Bruce is not alone. The school district supports at least 84 students through its federally mandated English Language Learners’ program. But students and staff say that program has shrunk over the last several years, and that it no longer meets the needs of students trying to learn and navigate high school in a new language.

A Decline in Services

Six years ago, Ketchikan High School’s ELL program included five class periods taught by about half a dozen certified staff. Now, students who struggle with English are told to seek help from a teacher during study hall. But the need hasn’t changed — the number of high schoolers in the program is roughly the same.

Bruce’s friend Czarina Cabillo, also a junior, has lived through those changes. She came over from the Philippines when she was younger and has attended elementary, middle and high school in Ketchikan.

Cabillo said she had teachers and resources to help her with the language in elementary school, but not anymore.

“It didn’t exist in middle school for me,” Cabillo said.

Cabillo said she started to fall behind until, by her freshman year of high school, she felt completely lost. Like the other kids, she was assigned essays on Shakespeare.

“That’s when I started struggling more in English,” she said. “We lost our classroom, we lost our teacher, and then, technically, right now, it’s not even a class anymore,” she said.

Sarah Campbell has watched those changes, too. She’s been a teacher in the district for 20 years.

“You can say you have this program, but no, you’re not fooling me,” she said. “I saw what it was 10 years ago, and I see what it is now. I don’t even recognize it.”

Campbell said the program used to include a range of specialized classes: ELL levels 1-3, Language Arts, Social Studies, and Conversational English — all for students like Bruce and Cabillo.

“Why change a successful model? It doesn’t make any sense to me,” Campbell said.

She said she watched her English language learners begin falling behind.

“I see students not making as many gains in their conversational and academic English, both in their verbal and written discourse. I see and have seen, over the past couple of years, some students actually stop attending school,” she said.

‘A really very good program’

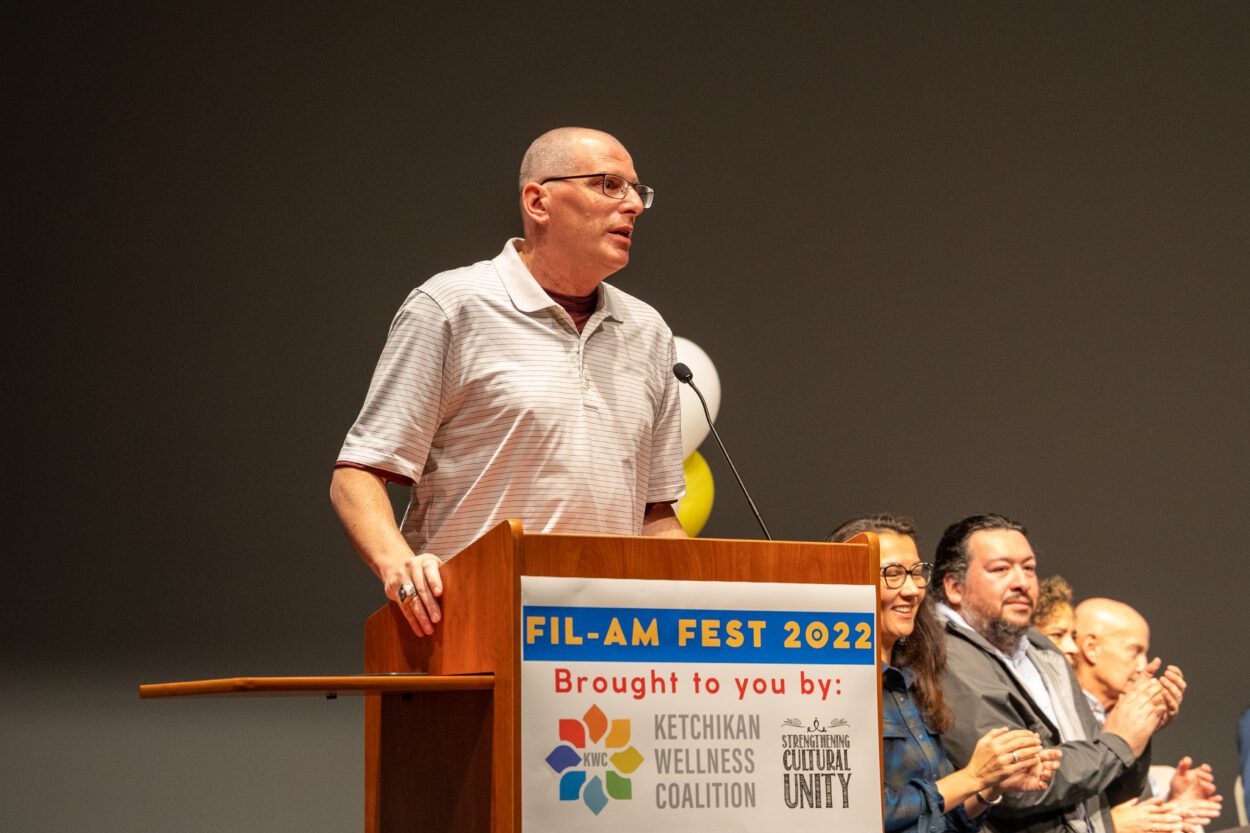

Michael Robbins, a tall, upbeat man with glasses, is the Ketchikan School District Superintendent. He stepped into the role in 2022 and said he can’t speak to what happened during former superintendent Beth Lougee’s tenure — Lougee did not respond to an interview request from KRBD. But across the board, Robbins said, Ketchikan schools are facing unprecedented limitations in programming.

According to the superintendent, it all comes down to the state’s per-student funding formula — the base student allocation — and the fact that it hasn’t been substantially raised in a decade.

“Anytime you don’t increase the base student allocation, it’s going to impact student achievement and learning,” said Robbins. “This is a state of Alaska funding problem.”

Still, he says Ketchikan’s ELL program is working.

According to Robbins, ELL students in the district have a very high graduation rate. He said 97% graduate on time, and the hard work of the current ELL program staff is partially to thank for that.

Robbins said that the program now consists of a coordinator, who serves the whole district, and two paraprofessionals, one of whom is ELL-certified.

“I would say that we have a really very good program in place,” said Robbins. “Are there places that we can improve? Sure, absolutely.”

A formal complaint

ELL is a federally mandated program, and there are regulations about the level of programming the district has to provide. The Department of Education provides grant funding for ELL programs, but according to Robbins, Ketchikan’s school district is just under the number of ELL students needed to qualify for those funds.

In 2022, a teacher in the district, Valerie Brooks, filed a formal complaint with the district alleging that the English Language Learners program was not meeting federal directives set forth in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act or requirements laid out in the School District’s nondiscrimination policy. Brooks, who has since retired, wrote in her complaint that this “could be construed as a violation of [students’] civil rights.”

Sedor, Wendlandt, Evans & Filippi, LLC, an Anchorage-based law firm that represents the school district, investigated the complaint and found that there had been a significant diminishment of ELL services — but that the district was still in compliance with state and federal law.

Campbell disagrees with these findings, though. She said the fact that several schools in the district don’t have ELL-certified teachers or paraprofessionals is a violation of state law and that no data has been shared with district or ELL program staff about how the program is helping students meet academic goals or the process for monitoring the success of those students after they leave the program — all of which Campbell says the district is required to evaluate annually and share the results with teachers under state and federal requirements.

“That’s just one lawyer’s opinion, and it’s the lawyer that the district hired,” Campbell said about the findings. “It doesn’t necessarily put the pressure on those who are making those decisions to have to account for the decisions they’ve made.”

A Task Force

Penny Leighton used to be one of the district’s certified ELL teachers. Like Campbell, she disagrees with Robbins’ view of the program — she says it has become a shadow of what it once was.

According to Leighton, the English Language Learners’ department was “stacked” back in 2017. But over a few years, it got whittled down — fewer class periods, less staff — and then it took a nosedive when Covid hit.

Leighton said that as other programs got back on their feet after the pandemic, the ELL program didn’t. By then, she was the only certified ELL teacher left in the program, driving between all of the district’s schools.

“I have all this documented by the way, I have every email, tons of text messages that I screenshotted from all of this, because I kept track,” said Leighton. “You know, because the administration kept saying, ‘we’re doing a great job, you know, we’re there for our students.’ We’re not.”

She felt like she was fighting a losing battle.

“And then I retired. It wasn’t happy, it wasn’t joyous,” she said, tearing up.

I wasn’t celebrating my retirement. I wasn’t ready to go.”

She didn’t fully step away though. Leighton chairs the Ketchikan Gateway Borough School Board’s ELL Task Force. The School Board created the task force after Campbell and students spoke out about the decline in services at one of their meetings earlier this year.

The task force has met twice and developed a half-dozen recommendations to the school district on how to revitalize the ELL program. But the meetings largely revolved around the nature and objective of the group itself.

For Leighton and Campbell, the task force’s purpose is to bring the ELL program back to what it used to be. But the school board representative on the task force took issue with that, saying the group’s only objective and authority is to “open up discussion about how we could move forward.”

Meanwhile, Rose Ann Bruce is focused on finishing her work before winter break.

“We need some ELL class so they can still teach you how to say even basic words, because if you just got here, you’re not gonna know everything,” she said. “It’s unfair towards the people who can’t, like, have their voice out, when it’s also hard for them to translate what they want to say.”

This story is part of CoastAlaska’s “Evolving Education” series. You can find the series online at kcaw.org.