Dozens of people gathered in the lofty atrium at Schoenbar Middle School. Yeił Atoowu Ginger McCormick of the Ketchikan Indian Community kicked things off by addressing the descendants of Nettie and Irene Jones.

“Your family should be recognized in times like this, because if it wasn’t for your grandmothers, I wouldn’t have higher education,” McCormick said. “Our children wouldn’t be making drums. They wouldn’t be weaving in school. We wouldn’t be here at Schoenbar about to sing a bunch of Indian songs.”

Nearly 30 years before the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case that ended segregation in schools nationwide, Nettie and Paul Jones sued the Ketchikan school district to allow their daughter Irene, who was of mixed Haida, Tsimshian, and white descent, to attend a school that tried to turn her away for being Native. Their legal victory was a cornerstone in the fight to end the practice of segregated schools in Alaska. Nearly a century later, the crowd gathered at Schoenbar to celebrate them.

Many of the Jones’ grandchildren live in Ketchikan. Many of them attended area schools like this one. McCormick said that she, along with all of the Indigenous women involved in the school district, carry a piece of Nettie Jones with them.

Ahl’lidaaw Terri Burr is a local Tsimshian language teacher. She knew Nettie Jones when she was a little girl. She said that the family’s fight for equality created a more humane and equitable community in Ketchikan.

“And what a rippling effect that had not just on Ketchikan and the territory of Alaska, but the entire nation,” Burr said. “So this is a really big deal.”

In 1906 Congress passed the Nelson Act, which formally segregated Alaska schools. It established a separate school system to educate white children and “children of mixed blood who led a civilized life.”

Schooling for Native children was handled by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). In Ketchikan, there were three schools: the Bureau of Indian Affairs school, then White Cliff and the Main School, which were largely for white and mixed race children.

Enter Irene Jones. Jones was 12 years old and of mixed Haida, Tsimshian, and white descent. She started at the Main School but a couple days later, was turned away when she arrived at school, along with three other Native students: Jennette Kennedy, Nelly Kennedy, and Ernestine Jones. According to historical accounts, they were told by Ketchikan School District Superintendent Tony E. Karnes that there was not enough room at the Main School.

So Irene’s parents, Paul and Nettie, hired attorney William Paul Sr., who at the time, was famed for championing Alaska Native rights in court.

Karnes had cited “overcrowding” to the Jones’ family as the reason their daughter and other Native students couldn’t attend the Main School.

William Paul went to Main School to investigate the overcrowding and made a surprising discovery. The attorney found that the school was removing desks that the Native students had sat in to artificially create an “overcrowding” issue. However, Paul reported that when a non-Native student had enrolled at the Main school, a desk was added into the classroom.

So Paul filed a discrimination lawsuit against the school board, and won. Irene and the other native students were admitted to the Main School.

Their legal victory was regarded as a cornerstone in the fight to end the practice of segregated schools in Alaska.

It’s a story that many across the state, and even in Ketchikan, haven’t heard.

In 2022, Schoenbar students made a documentary about Irene and Nettie Jones called “I Fought for That Seat.” Chad Frey, a teacher at Schoenbar, directed the documentary. He thinks it’s important to tell this story, especially for his students.

“One thing that I pride myself in, and one thing that I hope that I will continue to do, is to have visual representations of Native leaders in our school that our Native students can look at, that look like them and inspire them,” Frey said at Thursday’s celebration.

Many of his students are Tlingit, Haida, or Tsimshian and Frey said middle school is a time when they begin to understand the complications of society and its history of cultural erasure. They start imagining their place in the world, and how they fit into the future. And when that happens, Frey said, it’s important to have people like Nettie and Irene Jones front and center.

There’s another side to this story though. Irene Jones said years later that she was largely shunned after the court’s ruling. Not just by her white peers at the Main School, but by the Native community, for the uproar and tension the lawsuit caused. Historical accounts said that the other three Native students involved in the ruling chose to return to the BIA school, to avoid being ostracized.

Irene Jones stayed though, famously purported as saying “I fought for this seat, I’m going to sit in it.” Her granddaughter Kelly Needham said that Jones dealt with trauma from those years.

“You know, a big part of the experience of growing up being Irene’s granddaughter is that because of the things that she experienced in her childhood, my mother, my sisters and I didn’t learn a lot about our culture until we got older. She wasn’t able to teach us that,” Needham said. “And so as we got older and we learned about her story and the things that she did, it kind of awakened within us the desire to learn about our culture and to be strong women in her footsteps.”

And Yeił Atoowu Ginger McCormick, who kicked off the celebration, said this fight to reclaim the culture that was stripped from her and her ancestors is far from over.

“We have amazing weavers in the room that were told to stop weaving, and language speakers that could’ve stopped speaking, and they didn’t,” McCormick said. “We’ll never forget those, and we’re never going to forget the leadership that’s in front of us today.”

McCormick said there have been victories, like the fact that her children can learn Lingít in school, instead of being forced to take French or Spanish, but she added that just one generation ago, her mother was bullied in this same school system for wearing an eagle feather.

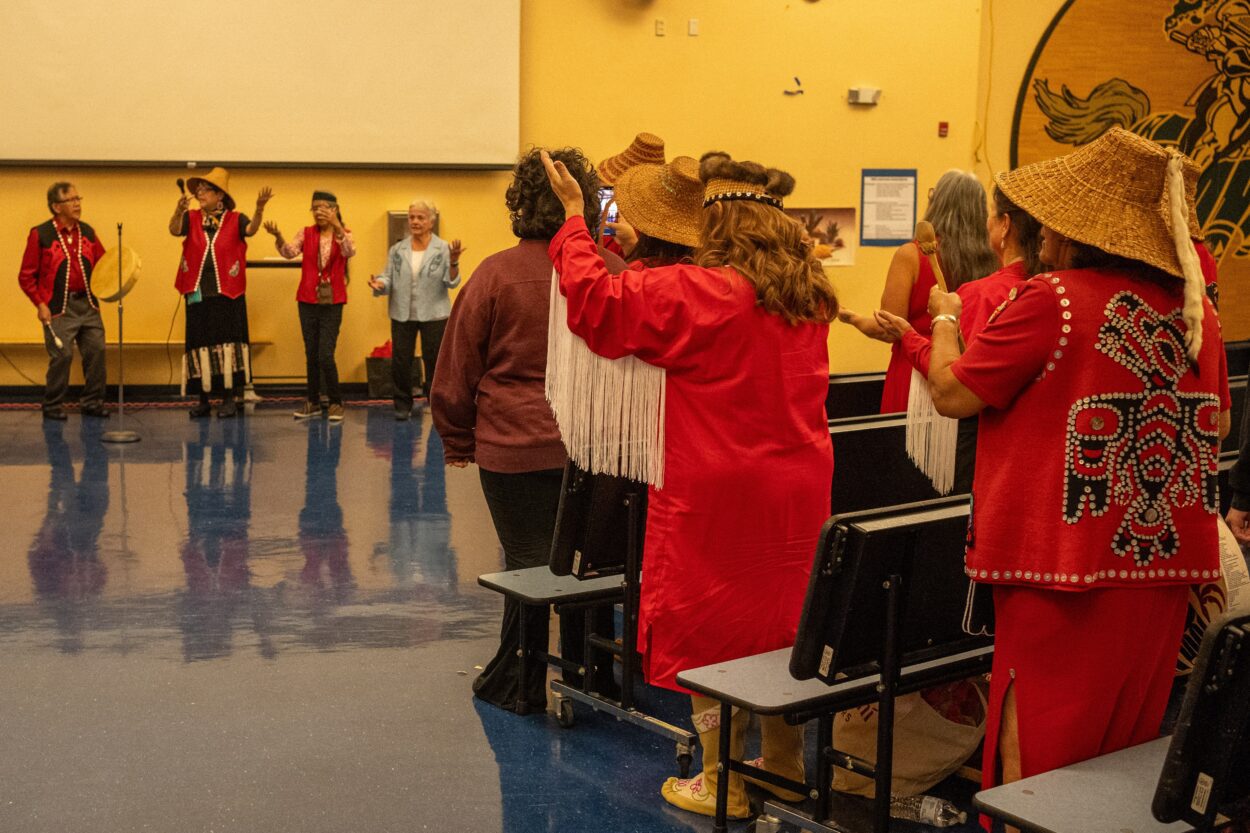

After the speeches, Ketchikan Borough Mayor Rodney Dial, City of Ketchikan Vice Mayor Janalee Gage, and Ketchikan Indian Community President Norman Skan signed a joint proclamation officially declaring Sept. 10 as Nettie Jones Day. Dance groups from the Tongass Tribe, Cape Fox Descendants, Haida Descendants, and Gameelaganm Neeaaym came forward to sing songs and dance in honor of matriarchs, strength, and family.

Then, they led the celebrants down to the school lobby where they unveiled a huge piece of artwork by artist Matt Hamilton. It was laid out like an old-fashioned fight poster, except instead of Joe Frazier or Muhammad Ali, it showed the faces of Irene and Nettie Jones floating on a pale yellow background with the hilltop Main School behind them. Underneath, it said “Irene and Nettie Jones vs. the Ketchikan School District.”

It’ll now greet Schoenbar students as they make their way to class.