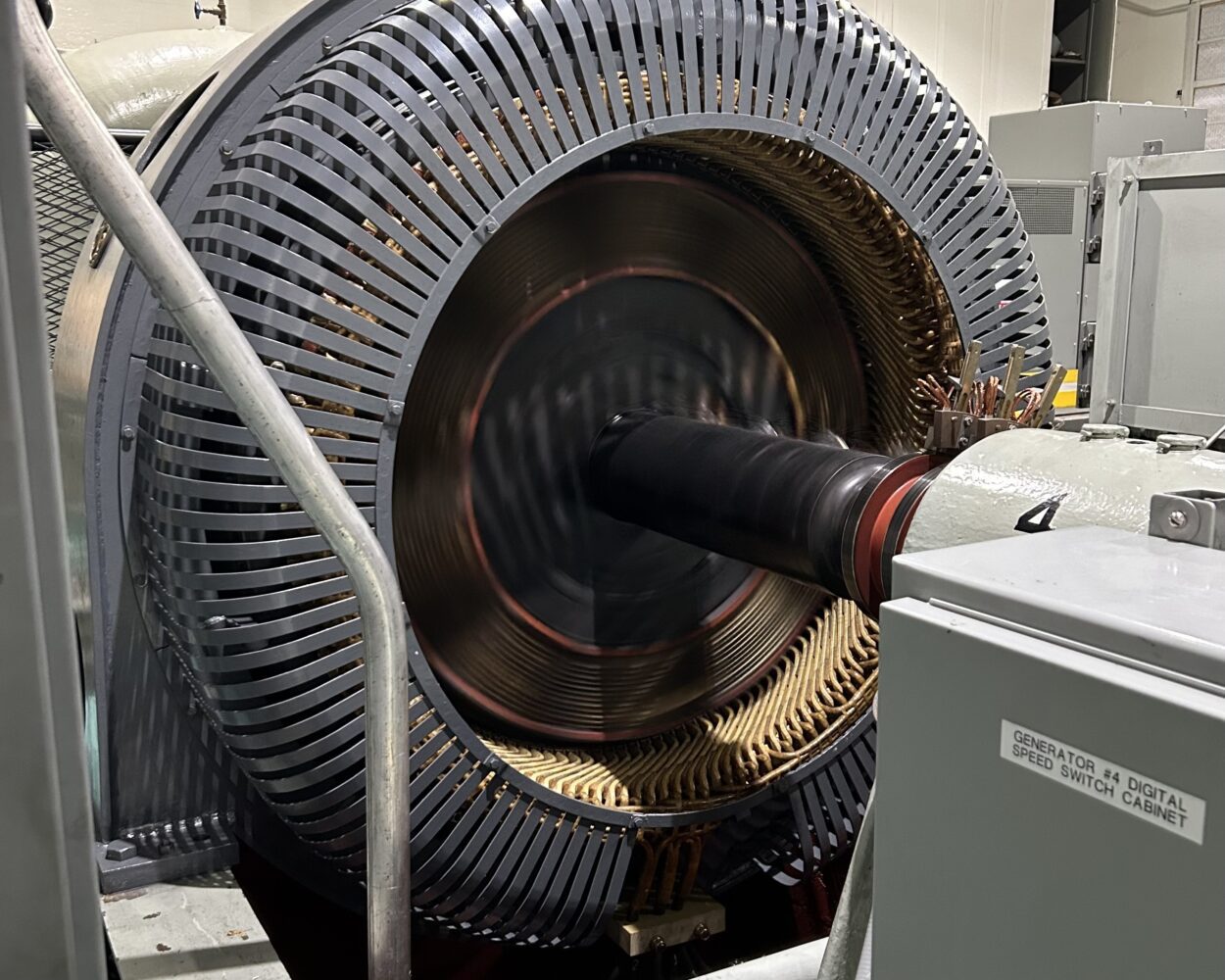

The sound inside the Ketchikan Lakes Hydroelectric plant is deafening. There are two generators in the powerhouse, controlled by walls of switches and dials that look like something out of Dr. Strangelove. The generators themselves look like portals one might step through to time travel, the rotors spinning so fast it’s almost hard to tell they’re in motion. Thousands of gallons of water from Ketchikan Lakes are pumping through the turbine by the minute.

Generators like this one feed pretty much the entire Ketchikan electric grid, and lately, that grid has the city’s electric utility very worried.

“I’ve seen insulators fail and pole fires over the last seven or eight years, but nothing like we’re seeing right now,” Jeremy Bynum, the electric manager at the city-owned Ketchikan Public Utilities, said over the phone.

For months, Bynum has been raising serious alarms about infrastructure, funding, and dwindling employees at the utility.

During a city council meeting in early May, he got emotional.

“This is the condition of our system. And as your manager, this keeps me up at night,” he said, his voice breaking.

Bynum was there because the weekend before, KPU’s three linemen responded to an outage downtown. They were down in a vault under Creek Street and a live wire exploded.

“This is a near miss,” Bynum warned. “We almost killed two of our guys on Saturday morning. When I say ‘we,’ I mean, our system did. We’re fortunate that they’re safe, and that they got to go home to their families.”

Bynum told the council that what happened that Saturday can’t happen again. Now, with what they are up against, next time something fails, he can’t send his guys to work on it if it’s energized. That means that if, or when, it happens again, KPU will have to put all of downtown out of service while they repair it.

The electric manager said the uptick in outages, pole fires, and grid failures may be the beginning of a series of infrastructure failures that Ketchikan isn’t prepared for.

This isn’t the first time someone from the electric utility stood at that podium and warned of the state of Ketchikan’s electric utility. At the first City Council meeting of 2024, a man named Donald Munhoven got up to tell the council they had a big problem.

The Linemen

“There’s better opportunities elsewhere. Far better,” Donald Munhoven, a KPU lineman, told the city council this winter. “Also, there’s the relationship with management. KPU has not been a great place to work in the last 10 years.”

Munhoven has been a lineman with KPU for 10 years. He’s the longest serving lineman on the job.

KPU currently has just three full-time linemen and one apprentice. They are advertising for five additional positions. In the early 2000s, there were as many as 14 linemen on the job.

The city lists the current starting wage for KPU linemen at $61 per hour. According to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers the average hourly rate across Alaska is $68. But Munhoven said the pay wasn’t necessarily why people left.

He said other utilities have planning departments, engineering departments, career development models, enough supplies for when things break, and adequate funding. KPU doesn’t.

The City of Ketchikan, including KPU, did an informal employee turnover review last year. Reasons for employees leaving included finding another job, dissatisfaction, and for unknown reasons. The review found most (about a third of all staff in the last five years) left because they moved.

Nick Kufner, one of the other three remaining linemen, wasn’t satisfied with that answer.

“Why the heck did they move?” he asked the City Council during the same meeting, standing beside Munhoven. “Because they hated it here. They got beat up for their whole time here. They got sick of being here and they couldn’t take it anymore. That’s why they moved.”

City Manager Delilah Walsh later emphasized that this was not a formal study, just an internal review that city staff completed themselves. They have since begun a more comprehensive employee retention survey, which concludes on May 31.

Walsh and Bynum also noted that they are contending with a national lineman shortage. Which seems to be true, linemen are in high demand right now across the country.

In a 2005 issue of the IBEW Journal, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Worker’s Utility Director Jim Hunter prophesied that the next two decades were going to see a big decline in dedicated journeyman linemen.

He attributed it to a decline in enrollment in vocational and trade schools, a huge wave of retirement-age linemen phasing out of the workforce, and the National Energy Policy Act of 1992, a congressional act that deregulated state electric utilities. Hunter said that policy change led to “Years of relentless cost cutting by the utility industry [that] have wiped out worker training programs and gutted the ranks of experienced linemen.”

In the intervening years, Bynum said something else has happened too.

According to Bynum, federal and state infrastructure dollars being poured into upgrading grids and bringing more renewable energy sources online have created much higher paying jobs elsewhere.

KPU Electric’s staffing woes, however, go much deeper than a national linemen shortage though. The three linemen at the city council meeting also pointed to a lack of advancement opportunities, flat pay, and a chaotic state of overwork.

Bynum admitted that in the past the electric division has had a notoriously flat pay rate. He also confirmed the linemens’ statements about advancement, saying that there is currently no mechanism for skill development. “And one of the worst things you could do to somebody when you bring them into an organization is that when they get there, there is no room for growth,” Bynum said.

Ketchikan’s grid is aging out on a massive scale. And according to the linemen, the fixes, maintenance, keeping the lights on, now all rests on their shoulders.

And they say they felt like their complaints fell on deaf ears at the city council.

“There’s too much work going on,” Munhoven said. “We can’t concentrate on the work we need to get done. Maintenance is falling behind by years. We’re lucky things are holding together at the moment. We just don’t have the manpower to keep up.”

Per the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s rules, any time a repair or update to the grid is needed, a minimum of three linemen have to be on-site. In KPU’s case, that is all of them.

“The infrastructure is a serious thing that people aren’t going to realize until something fails. And something is going to fail.” Nick Kufner warned. “Everything is so past its lifespan, it’s going to start burning up and it has been more and more often. It’s past critical now and people need to pay attention.”

And one of Ketchikans four hydroplants did fail, in a big way, a month after that January meeting.

The Infrastructure

In the dead of winter, the Silvis Lakes generator, located on the south end of the island, went offline after its stator winding broke. The stator winding is a stationary set of coiled wires at the heart of a hydro generator, which generate the electromagnetic field. The fix, Jeremy Bynum said at the time, could cost anywhere from $700,000 to $12 million. Currently, it appears the repair will cost a little over $850,000, according to the City Manager.

“And that means that this facility is out of service,” Bynum explained at a city council briefing the week of the meltdown. “And in this case, the facility is out of service in the worst time that it could be out of service.”

Winter is when energy usage in Alaska is at its highest. So to cover the gap created by the loss of the Silvis generator, Ketchikan switched to buying more energy from the Southeast Alaska Power Agency, or SEAPA, a regional power coalition.

Since the Silvis plant went offline, Bynum said the utility is paying SEAPA $104,000 a month to cover the power gap. And that’s $104,000 less every month that KPU has available to spend replacing insulators, and stators and poles — effectively creating a spiral.

Bynum said it was a consequence of poor planning.

“But we don’t have a risk fund that would help us in the event of a massive catastrophic failure. Silvis is an example of that,” he said.

In late April, one small piece on an electric pole in Ketchikan caught fire and sent Ketchikan, Petersburg, and Wrangell into a blackout. The three grids, which are interconnected, went dark for a few hours.

That pole fire was the third so far in 2024. KPU said it was caused by a failed insulator. Insulators are the corkscrew-like pieces that suspend the wires. Every electric pole has them, with thousands in Ketchikan’s grid alone. And according to Bynum, most of them are at the end of their life.

The Funding

After the plant failure, the city council voted to increase electric rates by about 6.2% at their meeting in February.

“I’m not here for raising the rates for the heck of it. I’m telling you what you need,” Bynum told the council at the time. Later, back in his office, he attributed the years of flat-funding in part to KPU’s status as a public utility.

Basically, to Bynum, that 6.2% increase was a start. City manager Delilah Walsh said, though, that to truly dig the city owned-utility out of this hole, they’d have to raise the rates a lot more.

“Looking at those initial revenue models and rate models, if we were to do everything we wanted to do, we’d have to raise rates by like 40%, which is ridiculous,” Walsh said. “But we would have to probably do close to a 16% to 20% rate increase all at once to just be at our basic catch up point.”

Of course, Walsh said that probably won’t happen. It’s a tough sell, especially when prices for everything else are rising fast, too.

“If I came to the budget process with the council, and I said, ‘Well, you got to raise rates by 30%,’ there’s no way – I mean, they’re gonna run me out of town,” she said.

According to public budget information, residential customers make up KPU’s largest user group, with businesses close behind and industrial coming in third.

Walsh said that in a more ideal world, Ketchikan would have a large industrial user group that could subsidize residential rates. She used a mining operation or a large college campus as an example. “And so when you have a big industrial user, that’s huge. They’re absorbing more of that base cost so that your volumetric cost can be reduced.”

Ketchikan has the lowest electric rates in the state according to Bynum — even after the recent increase. To demonstrate this, he produced a chart composed with composite data from the Department of Energy and KPU, which shows Ketchikan rates as being 20% below the national average and almost half of what Alaskans pay on the whole.

Last year, KPU’s Electric Division spent about $5 million more than they made in revenue. That’s not an anomaly — the electric division has been losing money for years. So has the water division.

Historically, those two have been effectively kept afloat by the profit made by the telecommunications division. But as Walsh warned in the transmittal letter for this year’s KPU budget, that approach just isn’t sustainable. After all, the telecom department has its own infrastructure to maintain, like an undersea fiber optic cable running to Prince Rupert.

Walsh said all this leaves the utility between a rock and a hard place.

“Our mission is to deliver safe and reliable service. That’s the bottom line. We keep our employees safe, we keep our citizens safe,” Walsh said. “Obviously, pole fires are not a safe utility, you know, if we have those things happening, and multiple outages.”

Bynum said he doesn’t know what the future holds for Ketchikan, but one thing he knows for certain is that this doesn’t get better before it gets worse.

Get in touch with the author at jack@krbd.org.