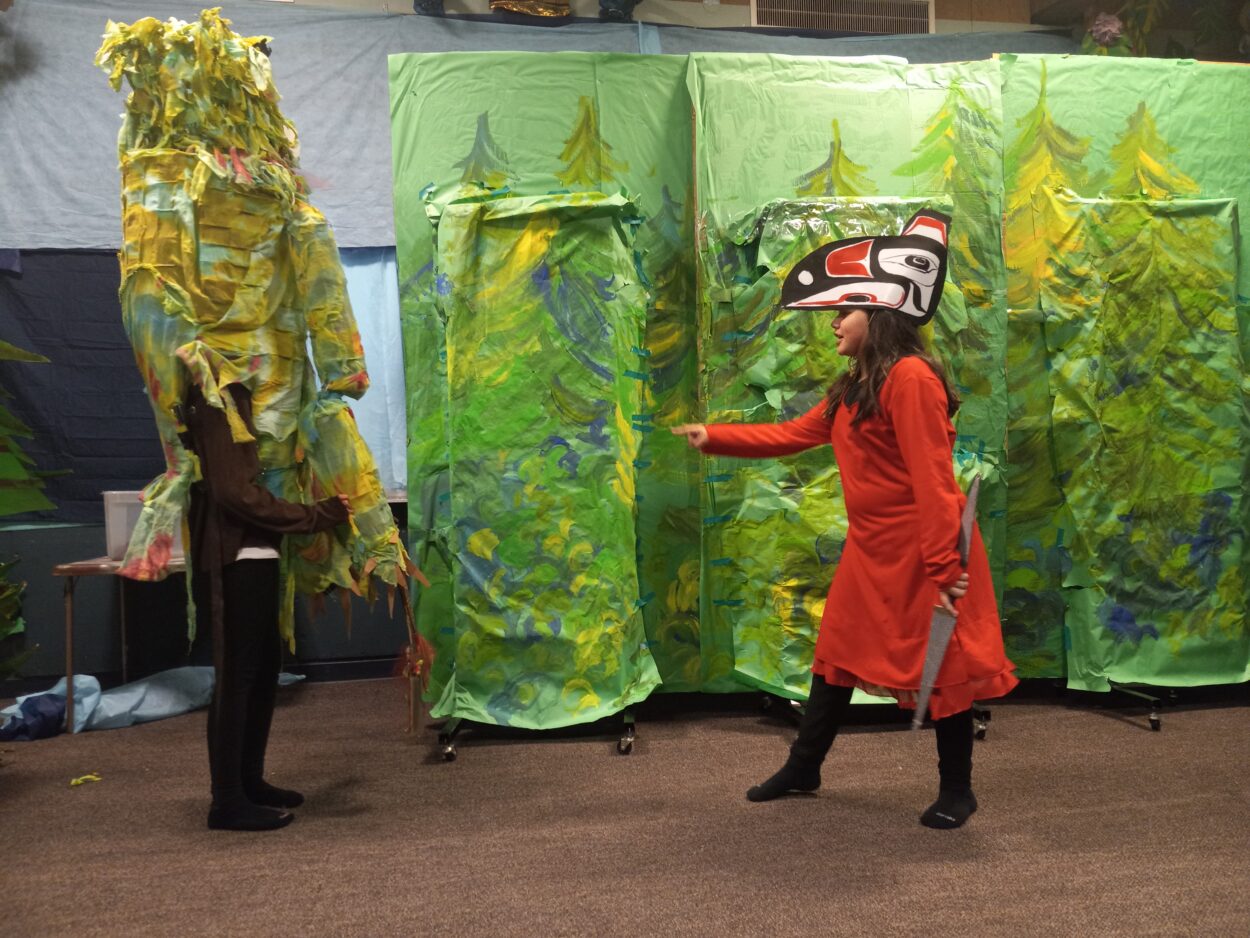

Two Indigenous stories came to life on stage at Ketchikan Charter School. Students turned “Killer Whale Eyes” and “How Devil’s Club Came to Be” into short plays featuring handmade props and formline the students learned from an artist-in-residence.

Paddling a cardboard canoe, the student actors are exploring the ocean. They’re looking for their classmate, the one who turned into a killer whale. Pods of hand painted cardboard orcas bob and weave in an ocean of royal blue cloth shaken by the students.

In another play, a student fights a monster who is stealing their tribe’s shaman. The heroine visits the Thunderbird people. She defeats the giant.

Then the metaphorical curtain came down, and they were all kids again, acting out traditional Indigenous stories as plays. The stories, written in those forms by Sondra Segundo and Miranda Rose Kaagweil Worl, are part of Sealaska Heritage Institute’s Baby Raven Reads program.

Halli Kenoyer is an art teacher at Charter School. Her class designed the props, and drama students in Erin Henderson’s class wrote the scripts. She applauds the students’ work.

“I mean, look at their formline,” Kenoyer commented.

Student Amelia Loeffler helped make a lot of the props — she proudly states she learned how to use an Exacto knife. Loeffler says her favorite of the two plays is “How Devil’s Club Came to Be.” That story follows Raven’s niece as she battles a giant who had been taking the village shaman. She discovers devil’s club and its medicinal properties along the way.

“It’s sort of fun to see how different cultures are,” she said.

Riley Presnell also helped bring the scenes to life.

“I think I really like painting,” he said. “I really like painting the canoe. I really liked painting the blanket.”

Kai Clevenger, a Lingit student, is the daughter of Kevin Clevenger, the school’s artist-in-residence. She helped create the formline that appears on the props. The seventh-grader says it’s important to her to see her culture taught and celebrated in school.

“I like how my culture is communicating with other, like, stuff now,” Clevenger explained. “And l like how my culture is like out there now.”

Student Ryan Boling also worked backstage. He says the fact that they’re traditional stories is what makes it special.

“I feel like Native stories need to get out there more than they are,” Boling said.

Bringing the stories to the stage was a community effort, Kenoyer says, with help from Ketchikan’s tribe staff. That included Irene Dundas, Ketchikan Indian Community’s cultural resources coordinator.

Fourth- and fifth-graders were able to pitch in, too. Kenoyer says the school’s artist-in-residence had taught the younger kids about formline design, which came in handy.

“And when we ran out of time to work on our props, fifth grade and fourth grade did our designs on the paddles, they worked on the button blankets,” she said. “They worked on the designs for all of the hats. And it was all on account of working with Kevin Clevenger that they knew how to do this. They were really excited to participate.”

That was one of the most satisfying parts of the production process, Kenoyer says.

“It was really cool to see that just that ripple effect of a really great program come into play in our little theater project,” she added.

The students performed their plays for classmates and community members, including the staff of Ketchikan’s local theater. They received a rowdy chorus of applause.

Raegan Miller is a Report for America corps member for KRBD. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep her writing stories like this one. Please consider making a tax-deductible contribution at KRBD.org/donate.