The R/V Tinro, a Russian research vessel, is shown in this photo provided by the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission. (Photo: R/V Tinro)

Tensions continue to simmer between Moscow and Washington in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In many respects, the divide between East and West is deepening: Oil companies are canceling partnerships with Russian firms. State legislators are calling for the state’s sovereign wealth fund to dump Russian investments. President Joe Biden announced Tuesday the U.S. would close its airspace to Russian aircraft.

But the United States and Russia are continuing to work together on at least one issue: salmon.

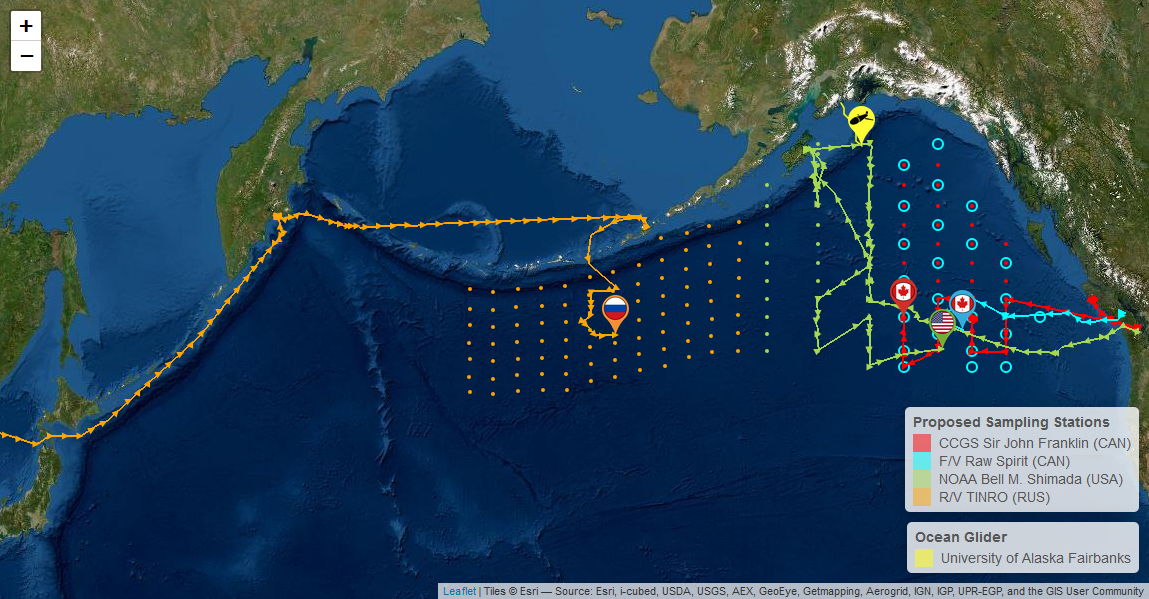

There’s a map scattered with orange, green, blue and red dots spanning most of the North Pacific above 46 degrees latitude.

On the map are three flags of Arctic nations: the U.S., Canada and the Russian Federation.

“This interaction between the countries in this is really something that has never happened to this scale before,” said Mark Saunders, the executive director of the five-country North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission.

He’s talking about the 2022 Pan-Pacific Winter High Seas Expedition.

Vessels from both sides of the Pacific are braving gale-force winds and 13-foot seas as they crisscross the ocean from the edge of the Aleutian Chain to the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

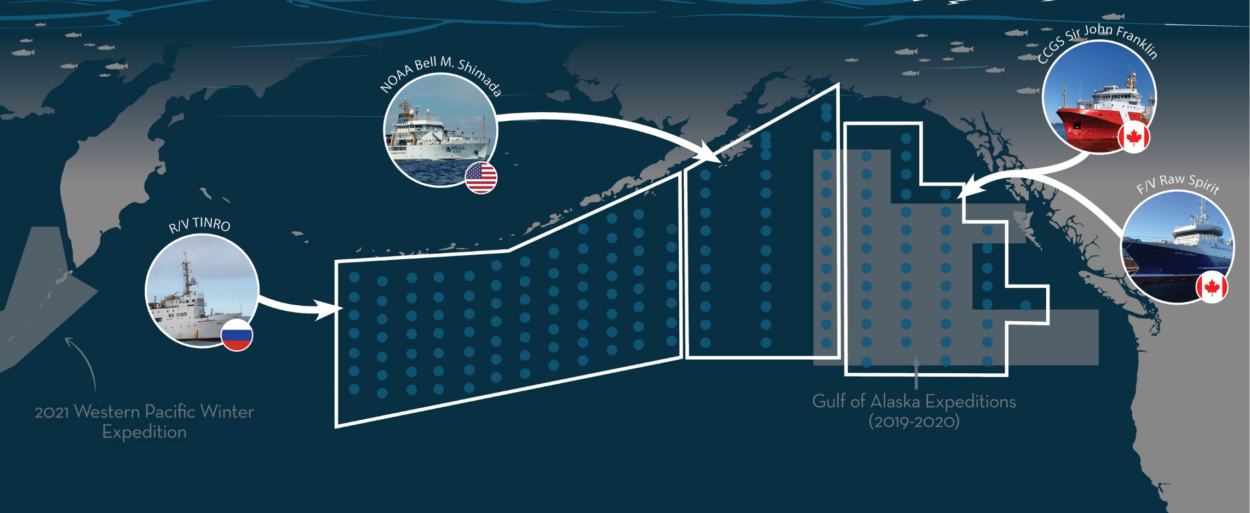

A map showing the current expedition along with past surveys conducted in the western Pacific and Gulf of Alaska. (North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission)

All in the name of research on challenges to wild salmon runs that are important to people on all sides of the north Pacific Rim.

A historic shortfall

Last year, the chum salmon run on the Yukon River collapsed.

“This past summer, the Yukon River did not fish for food. Zero,” said Mike Williams Sr. He’s the chair of the Kuskokwim Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, an organization that manages and researches fisheries using a combination of traditional knowledge and Western scientific methods.

Never before had so few fish swum up the nearly 2,000-mile river. Regulators closed all fishing on the Yukon to preserve what little of the run remained.

Williams says in recent years, he’s watched runs on the Kuskokwim dwindle, too. In the past, he says fishing was relatively unrestricted: Residents would return to their fish camps shortly after the ice on the river broke up in the spring.

But in recent years, he says residents have had to wait until June — long after breakup — to start stockpiling the essential staple.

“We depend on the salmon to sustain us through the winter, and we’re very concerned about the returns of our salmon in all of the rivers in Western Alaska” Williams said in a phone interview Wednesday.

It’s not clear what was behind the collapse. The Inter-Tribal Commission — and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, for that matter — spend most of their effort studying what happens in freshwater. But that’s just a small part of a salmon’s life.

‘Something happens in the ocean’

“The salmon spawn in our headwaters, they go down to the ocean, and something happens in the ocean,” Williams said.

And it’s not just Western Alaska that’s struggled with salmon runs in recent years — in Southeast, Chinook runs from Haines to Ketchikan are listed as stocks of concern. Salmon fishing on the Unuk River has been banned outright for years.

Some, including Williams, say too many salmon in the Bering Sea and the North Pacific are pulled out of the ocean as bycatch from trawlers that scrape the seabed for sole and flounder. Others say fish from hatcheries all over the north Pacific Rim are outcompeting native fish. Some say climate change is affecting the food web — or a combination of all these factors.

But one thing is clear: something is happening to chum and Chinook salmon in the open ocean.

“We know that a lot of the poor survival for chum and other salmon is related to the marine environment,” Saunders, of the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission, said Tuesday from his home office on Vancouver Island.

There’s quite a bit known about how the ocean is changing, “but you need to know where the fish are and have actually had your hands on them, and understand how they’re interacting with the environment,” Saunders said.

“I think a lot of that is a large black box — in particular, this winter period we know very little about,” he added.

He says the goal of the survey — the largest ever conducted — is to shine some light in that black box.

Scientists are hoping to map out the distribution of salmon across the North Pacific using new DNA techniques developed over the past decade or so to understand where salmon interact with predators, prey and each other — not to mention a generally warmer, more acidic ocean.

“And the big question is, how is the changing North Pacific Ocean affecting our salmon? And improving our ability to understand how that change is going to impact people and fish and fisheries into the future,” he said.

That brings us back to the map.

A screenshot of a live map tracking vessels from the U.S., Canada and Russia during the 2022 Pan-Pacific Winter High Seas Expedition on March 2, 2022. (YearOfTheSalmon.org)

A long-planned voyage meets geopolitical realities

Earlier this winter, ships from the U.S., Canada and Russia set sail for the North Pacific. Each is assigned its own area to sample: The U.S. and Canada are tackling areas in the Gulf of Alaska and west of British Columbia, and a vessel from Russia is surveying an immense swath of ocean spanning areas south of the Alaska Peninsula all the way out the Aleutian Chain southwest of Adak.

The Russian vessel’s survey work started late last month — it actually tied up in Dutch Harbor a day after Russian troops started their assault on Ukraine’s capital, Kyiv. Unalaska’s port director told KRBD the visit was tightly scrutinized by U.S. border agents.

Alaska’s chief salmon scientist, Bill Templin, says a few thoughts crossed his mind as he watched the invasion unfold.

“My first concerns were for the people of Ukraine,” Templin said by phone Wednesday. “But then when I walked into my office and I sat down, I was thinking, Oh, OK, so what does this mean?”

He says it’s not the first time international tensions have come up in his work with the five-country commission. He recalls Russian scientists including islands disputed with Japan on maps of salmon stocks — all in good fun, as he recalls it.

“The first two years, they got it past me, and the Japanese had to come over and correct me very politely,” he said.

But this is more tension than usual.

Saunders, the head of the anadromous fish commission, says an American scientist was scheduled to board the Russian vessel to allow it to survey within the 230-mile U.S exclusive economic zone.

A photo of the Russian R/V Tinro at sea provided by the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission. (Photo: R/V Tinro)

That didn’t happen. And that means the Russian research vessel can’t work close to the Aleutian Chain, where some salmon are thought to spend the winter. Templin says that means salmon activity within that zone will remain a blank spot for now.

“It doesn’t ruin the results. It’s not a failure — but it is going to limit what we get,” he said. “And it’s taken years to get this winter coordinated, so it’s a little disappointing.”

But Templin says scientists from Japan, Canada, South Korea, Russia and the United States have always put their work first, and their political leaders’ policies second. And he says that’ll continue.

“The salmon all go to the same place. So they’re all grazing in the same field, so to speak. For all of us to work together to understand what’s happening out there, and the way it affects our nations, is — I think it’s a pretty huge deal,” he said. “And I’d hate to see it go away.”

So far, geopolitical tensions haven’t overshadowed the need for cooperation — at least, not when it comes to preserving wild salmon.

Contact KRBD’s Eric Stone at 907-225-9655 or eric@krbd.org