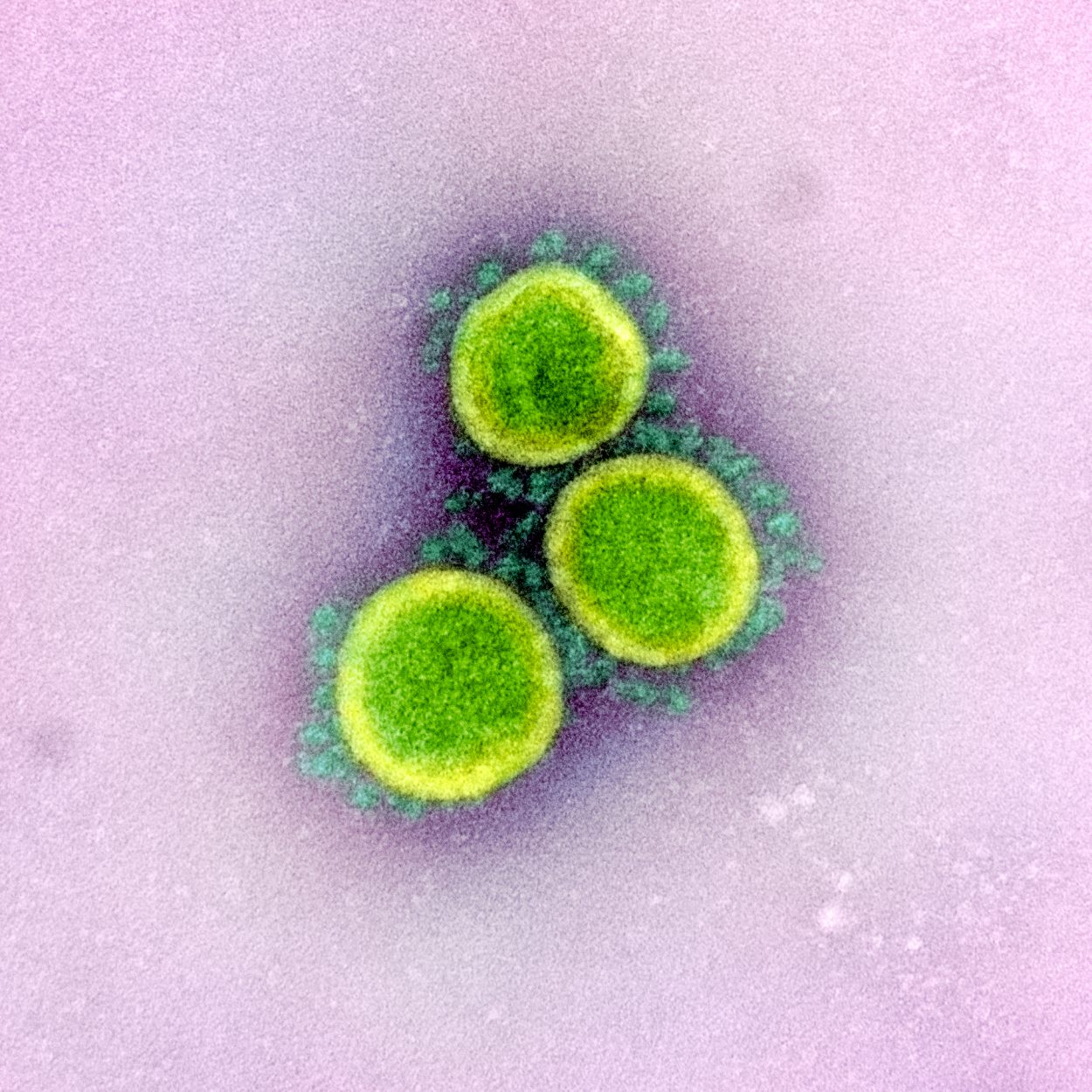

Three particles of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 are shown in this false-color image. (Micrograph: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

With fewer and fewer new cases reported daily, local leaders in Ketchikan have cut the locally-issued community risk level.

But there’s growing concern about recently-discovered cases of COVID-19 in an especially vulnerable group of people.

Local officials say two main factors drove the decision to lower the risk level to its second-highest rating: First, new infections are slowing. The number of so-called “community spread” cases — where health officials are unable to definitively identify the source of the virus — has fallen by more than half. The share of coronavirus tests that come back positive is also declining.

The other factor is increased vaccination rates. More than half of Ketchikan’s population has now received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. And as vaccination rates rise, the risk level becomes less sensitive to occasional outbreaks.

Though cases overall are slowing, Ketchikan-based state public health nurse Arizona Jacobs said she’s worried about some infections in an especially vulnerable population. In recent weeks, at least three people who are “unstably housed” have turned up COVID-19-positive, “whether that be persons who were experiencing homelessness, or sleeping in a shelter, or access homeless services,” Jacobs said in an interview. That also includes couch-surfers and people who come to a shelter for food or internet access.

Jacobs said keeping a lid on spread in people who don’t have a reliable place to sleep is difficult.

“It’s hard to contact them because there’s no permanent phone number or address. Also, a lot of people are just not willing to give up their contacts, so that really limits how much we know about their close contacts. It seems to be quite a few close contacts, unfortunately, I just don’t know who they are,” Jacobs said.

Quarantine and isolation is also more difficult. Ketchikan’s only summer shelter — the Park Avenue Temporary Home — doesn’t have the space to separate exposed or sick patrons from others. And its Executive Director Ty Rettke said even though the shelter has cut its capacity in half, it’s still close quarters.

“So one person coming in that’s sick could very quickly spread it to a dozen other people,” Rettke said in an interview.

Rettke said even if the shelter did have the space, its liability insurance policy makes it difficult for it to house people with COVID-19. And while other communities, like Anchorage, have isolated and quarantined homeless people in hotels, Rettke said a recent influx of visitors to Ketchikan means vacant hotel rooms are hard to come by.

Early in the pandemic, Ketchikan’s emergency operations center stood up a 24-hour homeless shelter in the community’s rec center. But the building is no longer available — it’s largely back open to the public.

Rettke said he’s working with local and state officials to come up with a solution.

“There’s probably going to be a combination of hotel spaces being reserved, (and) potentially, if we can find a workaround with the insurance, the EOC or the city might reopen the building next to me at 632 Park Avenue that operated the warming shelter during the winter,” Rettke said. “They might reopen that and use that as a quarantine location”

He said they’re contemplating some off-the-wall ideas, too.

“Maybe even like a camping scenario where we help folks that are able to and want to camp, where we provide support services, as far as making sure they’ve got supplies and food and everything they need,” Rettke said. “None of the options are really great, but we are working on figuring out something to do.”

And while free COVID-19 vaccines are readily available, Rettke said it can be difficult to convince people to get the shot.

“When you don’t know where you’re going to spend the night tonight, when you don’t know if you’re if you’re going to have a warm bed and a roof over your head or not, or where your next meal is going to come from, you enter essentially a fight-or-flight mode — you’re in a crisis state,” Rettke said.

And Rettke said that when shelter patrons’ minds are focused solely on survival — or when people are facing addiction or other mental illnesses — it’s difficult for advocates to communicate the proven safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

“You tend to not think as clearly or not be able to make as rational decisions and things like that. So coupling that with people that are, a lot of times, already less trusting of people they don’t know … it makes for a very difficult time in getting folks vaccinated,” Rettke said.

While just a handful of cases among homeless people in Ketchikan have been reported, public health nurse Jacobs said it’s difficult to do contact tracking and there’s not a lot of space to isolate and quarantine. So, it’s difficult to assess the scale of the problem.

“It’s relatively concerning that we basically have uncontrolled, unchecked spread among persons who are already super vulnerable,” Jacobs said.

She said so far, health authorities estimate just about 30 of Ketchikan’s unhoused people have been vaccinated, despite outreach efforts — even a vaccine clinic at the shelter. She said around 60 people use the shelter regularly, and another 200 use shelter services more intermittently.