Tour operators hold signs while cruise passengers disembark from the Eurodam. Scenes like this crowded dock likely aren’t in store for 2021 as lines institute anti-pandemic protocols. (KRBD file photo by Leila Kheiry)

Next summer’s cruise season could look very different in Southeast Alaska: pandemic precautions like testing, screening and social distancing will complicate the tourism economy if ships do return next year.

In order to get a handle on what to expect for next year’s cruise season, Ketchikan city officials hired some out-of-town expertise.

“So the discussion this evening, and the subject obviously, is how can Ketchikan position itself for the upcoming restart of the cruise season?” said Miami-based consultant Luis Ajamil, addressing the council on Nov. 19.

He told Ketchikan’s local leaders that all of the large cruise lines that serve Alaska are, for now, planning to be sailing again by the time the season rolls around in April.

Ajamil said most port communities are waiting for cruise giants to lay out their plans, but “this is not an issue that just the cruise lines themselves can do. And more importantly, it is of such vital importance to the community, that you all need to take that leadership position,” he said.

Which is to say, it’s better to make your own rules instead of waiting for cruise lines to bring their proposals.

Though cruise lines aren’t back at it yet, they’re expected to implement safety protocols that do their best to encase visitors in a “bubble.” Ajamil said they’ll likely use things like COVID-19 tests, health screenings and temperature checks in an attempt to keep the coronavirus from coming aboard.

Ajamil said cruise lines have put a lot of energy making sure passengers are screened from bringing the illness on board. Then they’ll need to ensure the virus isn’t contracted while onshore.

“It turns out to be that this is probably the most complex part of the journey,” he said. “And we know that because that’s when a passenger is going to get off and on and has to interact with the community.”

And that, of course, presents a problem. Industry groups have proposed restricting passengers to cruise line-sponsored excursions at the outset to give them a little more control over health protocols. But independent tour operators that can’t afford to sell their excursions aboard worry they’ll be left out.

That’s more or less what’s happened in Europe, Ajamil said. Visitors get on a bus, take an excursion, and return to their ship. In that case, the bus functions as an extension of a hermetically sealed cruise ship bubble.

“This gives you a glimpse that if you as a community don’t create your system, that’s what will happen,” he said. “Because that is the natural — that’s where, you know, gravity will take the cruise lines to do that.”

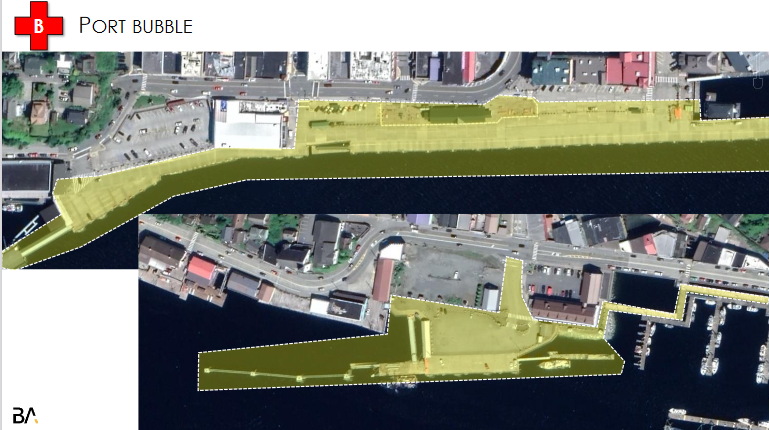

Ajamil framed geographic bubbles as an alternative. Basically, you take a map, draw a line, and seal a section of town off from the rest of the community — to get in or out, workers would need to go through the same precautions as cruise ship passengers — testing, temperature checks, and so on.

This map shows one concept for a small port bubble — cruise passengers would be restricted to the areas shaded in yellow. (Graphic: Bermello, Ajamil and Partners)

“You don’t have any buses there, people can’t come in and out of it, but you invite your businesses to come and set up shop there,” he said.

The bubble could be as small as the port itself — but given the small footprint of the city’s cruise ship docks, that’d still leave many businesses on the outside looking in. And the same precautions that insulate passengers from the virus will also act as an barrier preventing visitors from contributing to the local economy on the outside of the bubble.

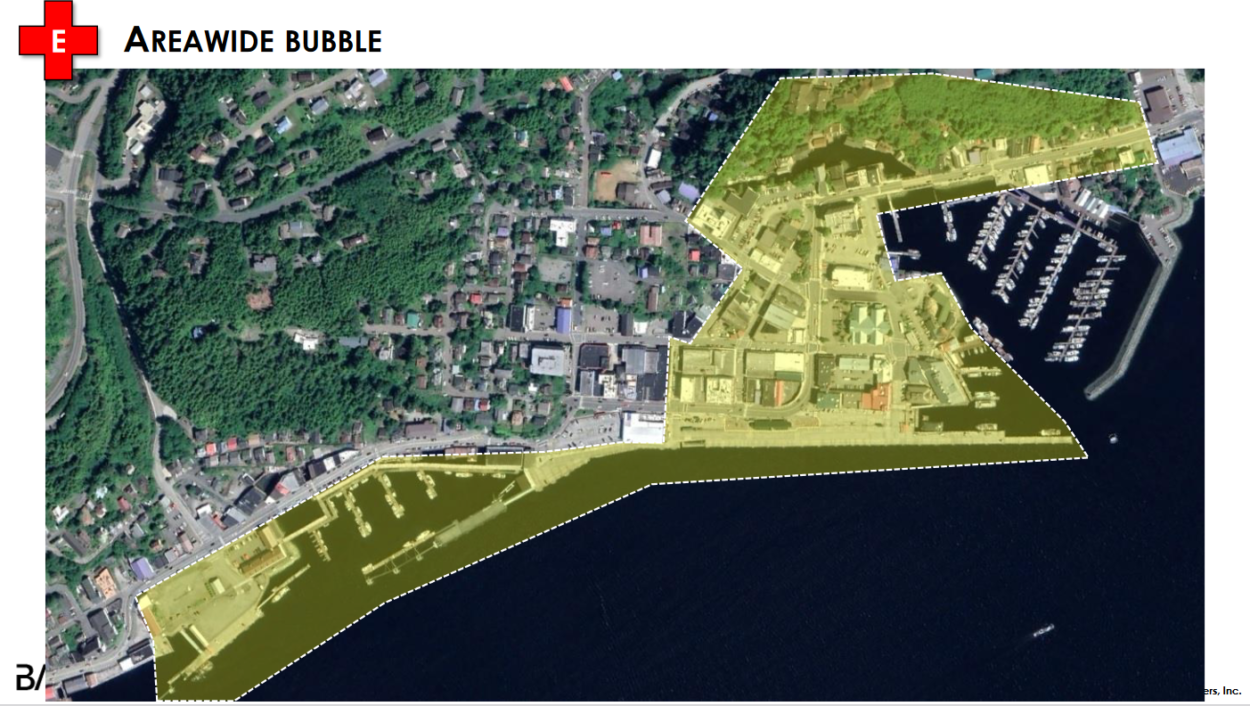

So Ajamil says Ketchikan could, in theory, expand that bubble to include most of downtown’s waterfront commercial areas — including the landmark Creek Street.

“It can be done, that you have bubbles within this area, and obviously the traffic can go through, it just can’t interact with the passengers,” Ajamil said. “But as you expand this bubble, more and more and more people will be able to enjoy the economic benefits.”

Ajamil said it may be feasible to expand the bubble to include much of downtown. (Graphic: Bermello, Ajamil and Partners)

Ajamil also pitched the idea of a city-wide bubble, where everyone who sets foot on the island has to be tested, screened and such. But Ajamil said that’s likely not a viable option for Ketchikan, though he suggested it might work for smaller communities — he pointed specifically to Skagway.

Ajamil said there’s a lot that’s still unknown. It’s not clear whether cruise lines would be amenable to any of the bubble proposals he laid out. There’s no real example of anything like this anywhere in the world, Ajamil said. But he said there is an upside to Ketchikan forging its own path.

“If Ketchikan does this right and proves it’s a safe destination, safe destinations will be a magnet,” he said.

Mayor Bob Sivertsen said it’ll be a challenge to plan.

“Quite daunting, to tell you the truth, in regards to the time crunch that we’d be under and the fact that there’s so much uncertainty around stuff,” he said.

City Council Member Abby Bradberry questioned where the resources would come from.

“Who would be paying for these costs of, you know, securing our bubble, and all the other recommendations … that we might have to impose on ourselves for the cruise lines or CDC?” she asked.

Ajamil replied that the city could charge a fee to passengers, similar to local and state head taxes.

The city has convened a task force to start planning, including representatives from the local businesses, cruise line agents, local public health officials and city port officials, among others.

And that’s good, Ajamil said, because there’s a lot of work to do, and the clock is ticking.

The Ketchikan task force, known as the RESOURCE Committee, is looking for comments on the best way forward in a public Facebook group.