There is no U.S. customs presence at the entrance to Hyder, Alaska as seen in this August 4, 2020 photo. (Photo by Jennifer Bunn/Hyder AK & Stewart BC COVID-19 Action Committee).

At the southeastern tip of Alaska’s panhandle lies the curious town of Hyder. It’s grown naturally alongside its Canadian neighbor of Stewart, B.C.

It has a 250 area code, electricity from B.C. Hydro and its only road access is through Canada’s highway system. It’s separated by 7,000-foot snow capped peaks from the rest of the state. So its connection with the rest of Alaska is limited.

“There’s about 65 of us here, the only way we get supplies is through a mail plane that comes in from Ketchikan twice a week …weather permitting,” said Wes Loe, president of the Hyder Community Association.

Most residents buy groceries and fuel and other supplies in Stewart, B.C. which is just over the border. For more than a century that was a mere formality as Canadian border guards would often wave people through.

But then came COVID-19 and with it blanket restrictions on cross-border travel.

“Since March, we can only go to Stewart once every seven days for three hours — to get whatever we need,” Loe said by telephone.

About 400 people live in Stewart, B.C. and they largely consider Hyder’s Alaskans a part of their greater community. A cross-border committee has been working to ease travel restrictions. It’s written letters to Canadian officials asking to relax the rules because of Hyder’s unique situation.

Jennifer Jean is Hyder’s co-chair of the Hyder, Alaska and Stewart B.C. COVID-19 Action Committee.

“We have no amenities in Hyder,” she said. “We have no gas stations, no grocery stores. There’s no medical facilities.”

There’s no school, either. Enrollment dropped below 10 students this year, leading the Southeast Island School District to shutter Hyder’s one-building schoolhouse.

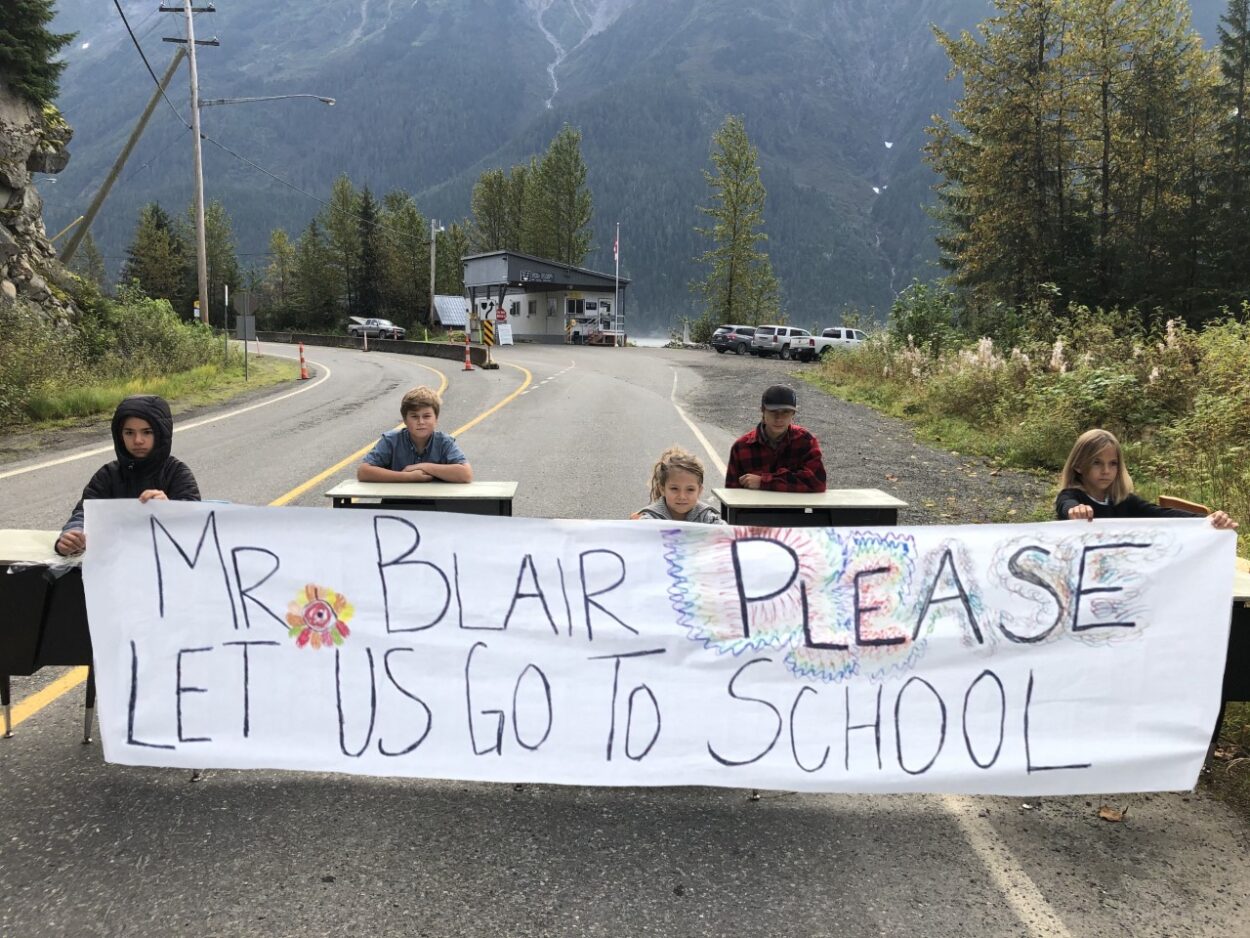

But there was a workaround: Hyder’s five school kids would be enrolled in Bear Valley School in Stewart.

Hyder resident Nick Korpela works across the border on a Canadian work permit. But he says his daughters haven’t been able to cross to see their friends since March.

“We promised them that they’re going to get to go to school and see their friends,” he said. “And two days before school started we got a call from the CBSA — Canadian customs — and they said that they were not going to allow the children through the border.”

Hyders five school-aged children sit at desks at the Hyder/Stewart border on September 10, 2020 — the day school starts in Stewart, B.C. — which they can’t attend because of current border restrictions. Their banner appeals to Bill Blair, Canada’s minister for public safety who oversees the Canada Border Services Agency. (Photo by Carly Ackerman/Hyder AK & Stewart BC COVID-19 Action Committee).

His daughters haven’t left Hyder since spring — except for a single afternoon on a float plane to Ketchikan. They’d been looking forward to a change in scenery.

“I was kind of sad,” 10-year-old Hilma Korpela said. “I was like, ‘Oh great, one more thing to not be able to do.'”

She’s starting the fifth grade. Now, her mother is preparing homeschool with her 8-year-old sister. But she says it’s not the same.

“I like hanging out with my friends … Hyder gets a bit lonely,” she said.

Jennifer Jean also has two school-aged children.

“It’s really really hard on them,” she says, fighting back the emotion in her voice. “That was the light at the end of the tunnel for them was to be able to see their friends again. Have a little bit of normalcy in their lives.”

The committee has redoubled its efforts to reopen the border with a recent rally on remote international frontier.

“They were at desks at the border the morning that school should have started and our Stewart friends and family came to their support the following day,” she recalled.

B.C.’s provincial officials are sympathetic but say their hands are tied as the border is controlled by the federal government in Ottawa.

Dr. Bonnie Henry — the top official leading the province’s pandemic response — told reporters last month she thinks it’d be reasonable to loosen border restrictions for Alaskans living in Hyder.

“My only concern, of course, is that we’ve started to see dramatic increases in cases in the last month in Alaska,” she said August 5. “And I know that that’s been a challenge for my counterpart, who I talk to regularly from Alaska.”

U.S. and Canada COVID-19 numbers are starkly different. Canada has had almost 9,200 reported deaths. Compare that to the U.S. nearing the 200,000 mark.

B.C. has about 1,000 more COVID-19 cases than Alaska. But the province has more than seven times Alaska’s population.

There have been no reported cases of COVID-19 in either town. But with no medical clinic in Hyder, there hasn’t been any testing, either.

“The larger border situation remains very worrisome for many Canadians,” said MP Taylor Bachrach Stewart’s elected representative in the Canadian parliament, “and there’s strong support for keeping the Canada-U.S. border closed as long as we need to, given the the stark difference in the situation on either side of the border.”

He’s thrown his weight behind his constituents who want the border opened to their neighbors in Hyder.

“I spoke with Bill Blair, the public safety minister for Canada, on the phone and communicated to him the urgency of the situation,” Bachrach said in an interview.

Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy has penned an August 27 letter appealing to Canada’s federal government in Ottawa.

“Winter is coming and we know this pandemic will continue for a while,” Dunleavy wrote. “Allowing these communities to integrate will ease feelings of isolation among Hyder residents.”

(Dunleavy’s office declined to comment for this story).

Bachrach says there’s been broad consensus from from elected officials in both Alaska and B.C. to work something out.

“At this point, it feels like there’s pretty strong support for some sort of solution,” Bachrach said. “So I’m curious why it’s taking so long to put something in place.”

But so far federal officials in Ottawa show no sign they’re willing to make exceptions.

A spokesperson for Canada’s Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister Bill Blair told CoastAlaska that as of August 7, school kids living in the U.S. are prohibited from attending school in Canada as they are subject to a mandatory 14-day quarantine.

“We brought forward significant restrictions at our borders to flatten the curve and prevent the spread of COVID-19 in Canada,” the ministry spokesperson wrote on Thursday. “These decisions have not been taken lightly, but we know that they are necessary to keep Canadians safe.”

It says the restrictions on school children crossing daily is in order to “prevent the importation of cases of COVID-19 to Canada and increased community transmission.”

Residents from both communities rally at the Stewart/Hyder border on September 11, 2020 in support of the Hyder children crossing the border to attend school in Stewart. (Photo by Carly Ackerman/Hyder AK & Stewart BC COVID-19 Action Committee).

Residents in Hyder and Stewart haven’t given up.They’re advocating for what they’re calling the #BearBubble that would create a shared space for residents in both communities and exempt them from the quarantine rules.

“We’re doing everything we can to kind of create our bubble community,” said Wes Loe, Hyder’s unofficial mayor,

He says winter is coming and people are getting worried about the impending darkness, deep snow and isolation that the border restrictions make much worse.

“You can see the depression, the anxiety, especially the anxiety that’s building up in people,” he said. “And you see things that are taking place that normally don’t take place.”

There have been bright spots. Stewart’s citizens recently donated truckloads of logs to Hyder as a goodwill gesture for their Alaska neighbors to cut up and use as firewood. Hyder’s residents haven’t been able to access a wood yard in Stewart, B.C. where they typically get their firewood to heat their homes.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to reflect that the donated firewood is from private individuals.