An aerial drone photo of Wolf Creek Boatworks on Prince of Wales Island in September 2019. The 80-year-old operation lies on state and federal land. (Photo courtesy of Sam Romey)

An 80-year-old hydro-powered wooden boat shop on Prince of Wales Island is in jeopardy as the federal government completes a massive land swap with the state’s mental health trust.

Audio PlayerWolf Creek Boatworks is an 80-year-old shoreline complex off the road system and off the grid. Power comes from a century-old hydro plant harnessing the force of water flowing downhill.

“It goes into a turbine, a water turbine from 1902,” owner Sam Romey said by telephone. “So it’s still working, fully functioning.”

It’s been running continuously since 1939, much of it on the same flat belt-driven technology powered by a hydro turbine that generates electricity and harnesses kinetic energy from the creek on an isolated cove at the end of Twelve Mile Arm halfway between the communities of Hollis and Kasaan.

But that location made it perfect for builders of wooden boats used at the time by Prince of Wales Island’s fishing fleet. In fact, it’s still the only place on the island skippers can haul their vessels out of the water. The next closest would be in Ketchikan, more than 40 miles over water.

“A lot of people use that grid for, you know, changing zincs, painting the bottom, stuff like that,” said Ronald Leighton, tribal president of the Organized Village of Kasaan. “Yeah, I know I went up there with my boat a couple times.”

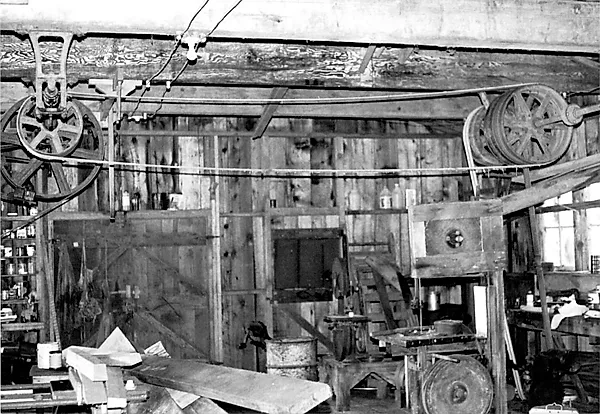

Wolf Creek Boatworks owner Sam Romey says the flat belt driven shop machinery, shown in the 1940s, has not changed much in the last 80 years. (Photo courtesy of Sam Romey)

The boatworks has operated on leased public land since the beginning. Or at least it did up until 2015. Then things got complicated after Congress passed legislation mandating a roughly 20,000 acre swap between Tongass National Forest and the Alaska Mental Health Trust.

“This land exchange is extremely important for the mental health beneficiaries in Alaska,” said Wyn Menefee, executive director of the trust’s land office. He says legally, the boatworks is trespassing on state and federal land on an expired lease and expects the trust to take full possession of the land next year.

“If we receive the property with the buildings, then we will decide what to do with them at that point in time,” he said.

The Forest Service’s view is that because the lease had expired when Congress mandated the land exchange in 2017, it can’t issue another permit. But Romey has emails showing he was still in the renewal process a year after the land swap bill was signed into law.

That all ground to a halt last year and an eviction notice was served.

“They figured they could just give me an eviction notice and go away,” Romey said. “And then they realize that I own the buildings. So to tell me to go away and take my buildings with the would destroy the possible National Historic Site.”

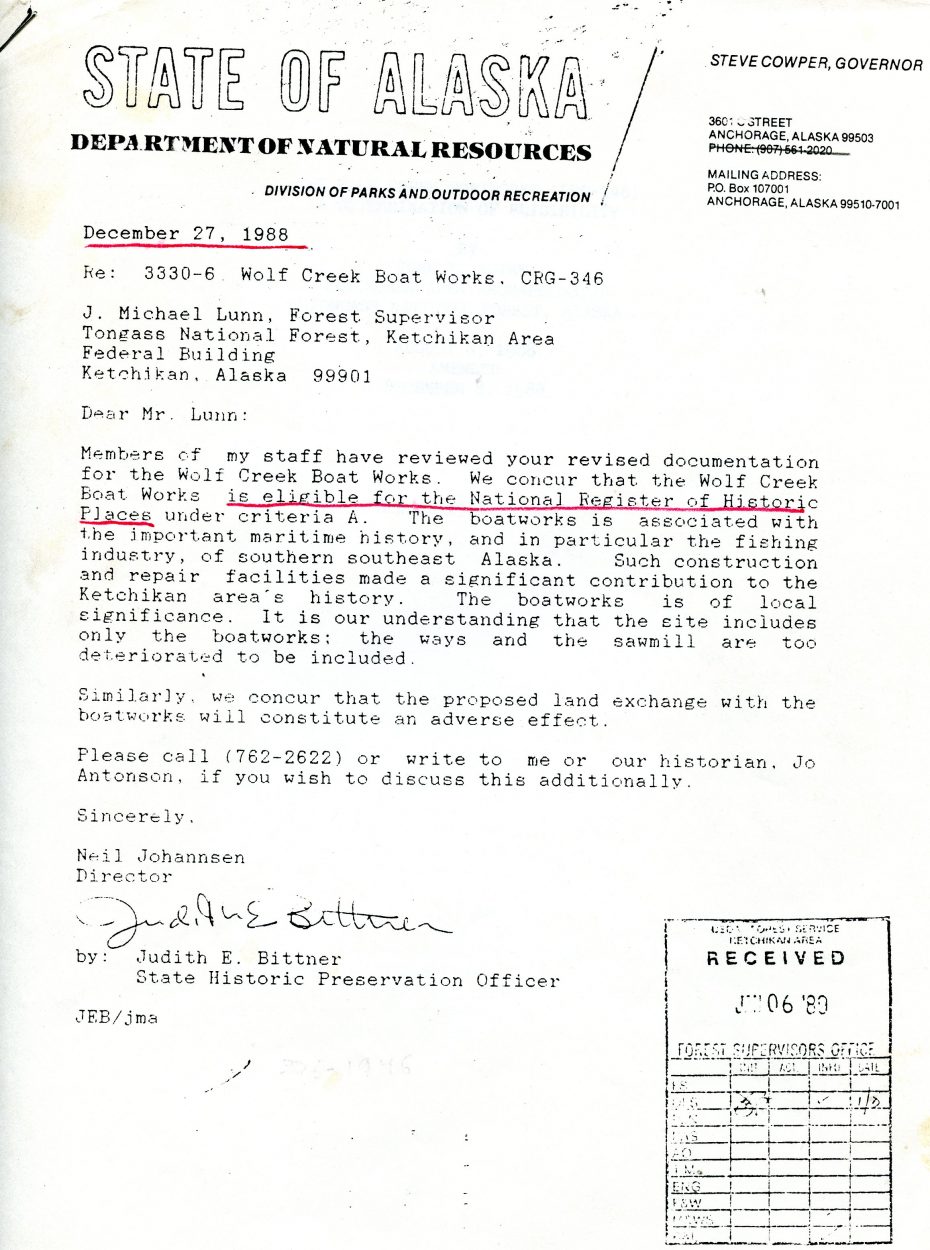

The boatworks was deemed worthy of protection back in 1988. But the state never submitted the documents and the listing never went through.

Even so, legally the Forest Service still has a responsibility to make sure history is not erased when its lands are transferred to the mental health trust. An agreement signed by state historic preservation officials in 2018 covers the entire swap and there are concerns that the spirit of the agreement isn’t being honored.

“It was our understanding that the boat works would be transferred to the Mental Health Trust, and it would be dealt with with a district property management plan,” said Judith Bittner, the state’s historic preservation officer.

She’s alarmed that the Forest Service is now demanding that the structure be partially dismantled or left to the trust with no assurances of its continuity. In fact, the plan only stipulates that a “poster” is created that catalogs any historic site destroyed.

“And so we’re, you know, we’re ending up with a very complex situation that puts the historic property in threat of loss,” she said.

Menfee says he understands the outcry over the future of the boatworks, but the trust isn’t cutting any deals with anyone before it takes possession of the land.

“I understand why people are saying what they are about trying to get it back to Sam (Romey),” Menefee said. “I understand their perspective; it’s just not in the purview of my obligations. My obligations are strictly financial and fiduciary to the trust.”

The trust’s land office has indicated that it intends to commercially log much of the forest land it’s receiving. But Romey and others point out that the state’s mandatory setbacks around fish streams means much of the seven acres around the boatworks couldn’t be legally logged. And he says the trust has turned down an offer for a swap of forested lands he owns nearby.

Trish Neal, president of the Alaska Historic Preservation Association, says there’s a real danger of losing a piece of the region’s history. The Anchorage-based nonprofit recently ranked it among its top 10 most endangered historic properties.

“It’s been operating since for 80 years — it’s a viable business,” she said. “It’s not somebody’s hobby, it’s not just somebody’s place out in the woods.”

She says the Forest Service has a responsibility to preserve one of the last historic boat yards in Southeast Alaska.

“The Forest Service, in my opinion, (is) just taking the easy way out, and it’s just going to slap up something on a kiosk,” she said.

The Forest Service declined to make anyone available for an interview.

“One of the USDA Forest Service Alaska Region’s highest priorities is the completion of the Alaska Mental Health Trust land exchange,” a statement to CoastAlaska attributed to Alaska Region spokeswoman Katie Benning said. “Recently, the Forest Service and the Alaska Mental Health Trust Authority closed on a portion of Phase II and are working to complete the final portion of the exchange. It is anticipated that the land exchange will be completed in early 2021.”

The agency declined further comment. But on its website, it wrote: “the public is invited to share ideas on how to mitigate the potential adverse effects of removing the Boatworks” by sending written comments to sm.fs.WC_Boatworks@usda.gov by May 22. It’s unclear what types of ideas it’s seeking. An early April teleconference elicited nearly a dozen letters in support for the boatworks.

Proponents of saving the boatworks have also appealed to Sen. Lisa Murkowski who had pushed for the 2017 legislation mandating the land swap.

“Sen. Murkowski is aware of the issue concerning Wolf Creek Boatworks, and expects the Forest Service to properly address any historic structures at the site,” spokeswoman Grace Jang wrote in a statement.