As mass shootings become more prevalent, it’s important to know how to protect yourself in a violent situation.

Last Tuesday and Wednesday, court system employees, mental heath behavioral workers, law enforcement, and educators went to Ketchikan High School to participate in an ALICE-led active shooter civilian training. ALICE stands for Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, and Evacuate.

ALICE trainer Joe Chavalia is a retired senior sergeant from a police station in Lima [Lie-ma], Ohio. He said he started working for Response Options, the parent company of ALICE, in 2009 to make an impact and help save lives.

Since the program started in 2001, he said facilities that have participated in ALICE training have been able to protect themselves when faced with a threat.

“I can point to 17 different individuals and or facilities that have been attacked that have been trained in ALICE,” said Chavalia. “We’ve had no fatalities during those attacks—we’ve had three injuries. But again, I think it’s important to understand that we have had absolutely not the first fatality during those.”

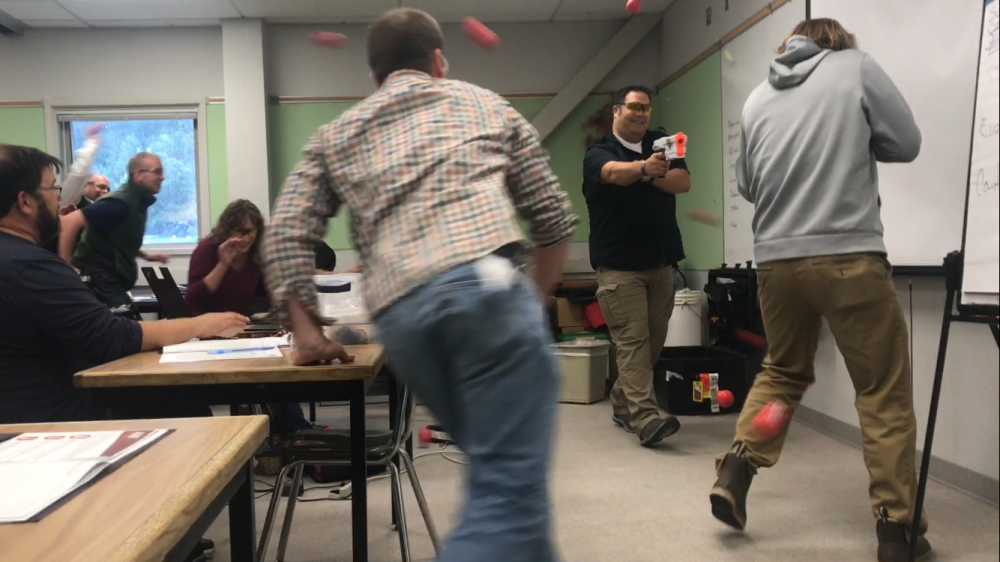

The active shooter drills involved individuals taking turns pretending to be a shooter. They used a Nerf gun as the group went through various options such as enhanced lockdown by barricading a door, counter strategies to take back control, and the preferred option—evacuation. The group started the first day with lock-down exercises. They closed the door and blinds, turned the lights off, and hid under a desk. For this drill, the imaginary shooter was an educator with no gun experience, and she was able to shoot 23 of the 29 participants.

Chavalia said Northern Kentucky University published a peer-review study last year that showed lockdowns are less effective than other options.

“When you look at the same type of an event that occurred in the same type of an environment but using multiple options as the response, the resolution occurred in 16 seconds,” said Chavalia. “And, the shot average was only 25 percent.”

That’s compared to more than three minutes, with a 74-percent shot average in an average lockdown response.

The next stage of training allowed participants to use evacuation tactics to escape their shooter. This time, Chavalia chose law enforcement officers as the pretend active shooters.

“The trained law enforcement professionals when faced with people moving—when faced with other obstacles, other distractions—were only able to shoot nine people,” said Chavalia. “And only four of those were shots that were on the body that were probably significant wounds. The other five were just peripheral shots.”

Drills that didn’t involve static, passive actions show the number of individuals shot was extremely low compared to the 23 shot during the lockdown drill.

There is concern that teaching active shooter drills to students will help a potential shooter. However, Chavalia said that’s a risk worth taking.

“Because even though the possible shooter might know what the game plan is going to be to counter him, and by counter I mean evacuation, fortifying, enhanced lockdown—actually doing physical encounters,” said Chavalia. “Having that knowledge of what might happen, and actually having it happen, are two entirely different things. ”

He used a football analogy to represent that the actual event will always be different from what you expect.

“Everybody knows that when the center gives the ball to the quarterback, it’s either going to be a run play or it’s going to be a pass play,” said Chavalia. “And very seldom does that play go all the way to fruition, straight from the snap, to a touchdown. Everybody knows the defense is going to hit him. It’s one thing to know that that 300 pound tackle is going to hit ya, it’s a whole [other] event when it actually happens.”

Despite the prevalence of mass shootings over the past few years, people still believe shootings won’t happen in small towns, like Ketchikan, where everyone knows everyone. However, Chavalia said that’s not the case.

“We had an event, a mass homicide, that occurred at a one-room Amish school house the last week of September in 2006 in Pennsylvania—Amish country USA,” said Chavalia. “ It couldn’t possibly happen there. Yet, it did. So why would you think that your location is so special that it couldn’t possibly happen to you?”

Training attendees can get their certification to teach the ALICE training to local businesses and organizations. Principals will teach new active shooter drills to teachers.