Not everyone is awake at 5 a.m. on a beach, testing the water for poop, but for Nicole Forbes, who’s wearing a set of bright teal waders with her hair tied in a ponytail, this is what every Wednesday morning looks like this summer.

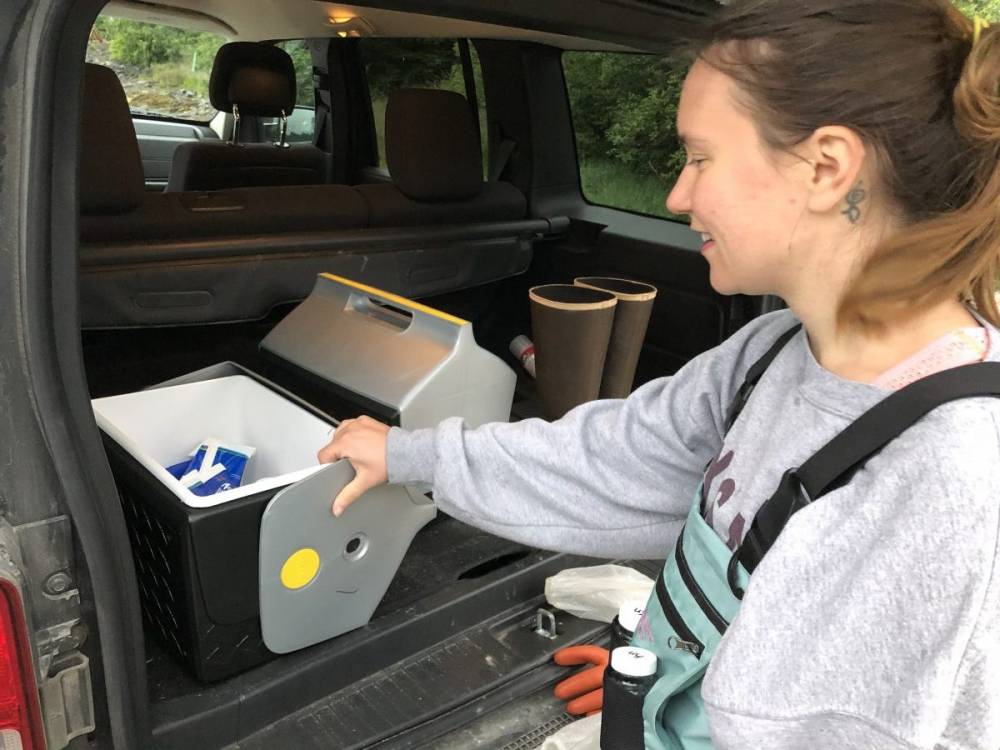

“I just take out my two little bottles, and I uncap them. I put them straight into the water and pull them up and make sure they’re filled to the line,” Forbes said.

She’s at South Point Higgins, one of 11 beaches Forbes is testing this morning near Ketchikan. With her two bottles, she heads straight into the cold water.

While she’s in the water, she also tests the air and water temperature and makes mental notes on wildlife in the area, how many people and boats are there and if there is anything unusual like a strange smell. Forbes finds a lot of wildlife during these early mornings, including humpback whales, plenty of eagles and seals, which are a favorite.

“They’ll pop their heads up and look at me. Then they’ll go back down and pop their heads up again and say ‘you’re still here?’ But that’s why it’s really fun.”

Seeing wildlife is a fun perk. But the reason for all of these tests is serious: public safety.

Forbes is an Environmental Specialist with Ketchikan Indian Community (KIC), a Native organization working with the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to monitor fecal bacteria and Enterococci bacteria in the water at beaches around Ketchikan.

“We want to make sure the beaches are safe for everyone. I know that beaches are super important in so many different ways for us here. Not only are there resources like seaweed and different ocean food, but we actually have people swimming with their kids out in the water.”

DEC and KIC started testing Ketchikan’s beaches last summer as a part of the Alaska Beach Grant Program, a federally-funded initiative to reduce water-borne illness on Alaska’s beaches.

Testing last year showed fecal bacteria at unsafe levels in at least one location every week that testing was done. Advisories for seven locations were issued in a span of a month. This summer, levels have actually been low.

But how does this poop get in the water? They’re also trying to figure that out. Forbes surveys boats, wastewater outfalls and wildlife on each beach to help gather data on what the source might be. She also sends a few water samples down to Florida where they test to see whether the bacteria is from humans, gulls or dogs.

Because there’s so little data so far, it’s hard to say at this point where the bacteria is coming from, KIC Cultural Resources Director Tony Gallegos said.

“It’s hard to point fingers at any one source. You’re pretty much going to be waving your hand instead of pointing your finger. It’s a wide area, so I don’t think it’s a single smoking gun out there,” Gallegos said.

The report DEC released after last summer’s testing said it’s unlikely cruise ships dumping wastewater is the cause because of the stringent health regulations those ships have to follow.

KIC and DEC will continue beach testing in future summers. If a beach continually shows high levels of bacteria year after year, it’ll be listed as “impaired” and banned from public use until levels consistently return to normal, DEC Environmental Program Specialist Gretchen Pikul said.

“Once water is put on the impaired list, the Environmental Protection Agency requires a “total daily maximum load” report. You can also look at it as a remediation plan,” Pikul said. “This is what’s in the water. This is the magnitude and frequency we’re seeing it in the water. And what can we do to improve the water quality?”

Until then, Nicole Forbes will continue waking up early and donning her teal waders.