Researcher Wiley Evans installed equipment on the Alaska Marine Highway System ferry Columbia, to monitor ocean acidification along the ferry’s 2,000-mile route. (KRBD photo by Leila Kheiry)

The Alaska Marine Highway System ferry Columbia will be part of an international science experiment starting this fall when it resumes its weekly run between Bellingham, Wash., and Southeast Alaska.

Equipment has been installed to continuously measure the ocean’s acidity along the ferry’s nearly 2,000-mile route. The goal is to better understand how acidification affects regional fisheries.

The 418-foot ferry Columbia is docked at Ketchikan’s Vigor Alaska shipyard while undergoing repairs to its propeller system.

That’s not great for ferry passengers, who have been sailing on the smaller Malaspina instead. But, it worked out for a team of scientists who installed a seawater-monitoring system on the Columbia before the ferry is due to resume service.

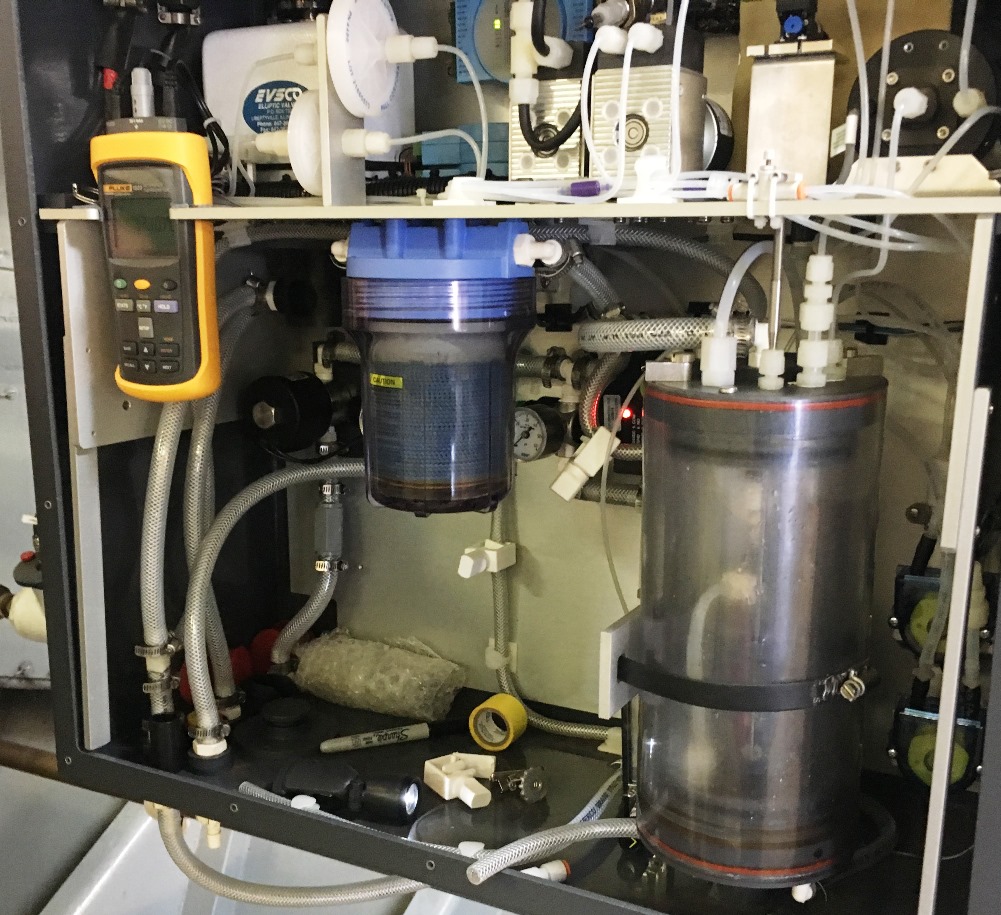

Wiley Evans is a researcher with the Canadian Hakai Institute, and is the technical lead in the program. Tucked under some stairs in a corner of the Columbia’s car deck, he shows me the newly installed equipment.

Evans said getting to this point took about three years.

Researcher Wiley Evans checks progress on the “wet box,” where ocean water is filtered and mixed with air to gather carbon dioxide for testing. (KRBD photo by Leila Kheiry)

“Allison Bidlack from Alaska Coastal Rainforest Center and I started talking about this in 2014,” he said. “In 2015, we did a similar installation on another passenger vessel. That was a glacier tour vessel that operated out of Whittier.”

That was a small catamaran.

“At the time, I felt it was fairly difficult, but now, having been through this installation – that was pretty easy,” he said. “The size of the (Columbia), The fact that it’s a ferry, and they’re very cautious about seawater flowing through the vessel and how it’s moving around the vessel.”

The seawater lines had to be engineered and installed. Through those lines, seawater enters the system at the bow thruster cavity, and is pumped up to the equipment on the car deck.

“The water first flows through an oxygen sensor, then through a thermosalinograph, which measures the temperature and salinity of the water, and then into these boxes here, these larger boxes,” he said, pointing to some of the equipment. “The first is the wet box. Water goes into the wet box and is equilibrated with air.”

In other words, ocean water is sucked up while the ship is under way, and then is measured for oxygen, temperature and salinity – that’s how much salt it contains. Then it’s pumped into the wet box, where it is sprayed into a little container.

Air in that container picks up carbon dioxide contained in the water. That air then is pumped into dry box, which analyzes CO2 levels. Those levels indicate the acidity of the water.

Separate sensors measure carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, to compare that with the seawater.

“What we’re after is trying to understand the time and space patterns in surface ocean CO2 chemistry near shore,” he said. “In this area, it’s extremely data-poor.”

Evans said they hope to discover patterns of CO2 concentrations along the entire Southeast Alaska and

The “wet box” on the car deck of the Alaska Marine Highway System ferry Columbia is part of a system that will monitor carbon dioxide levels in the surface water along the ferry’s route. (KRBD photo by Leila Kheiry)

British Columbia coastline. And the ferry is the perfect platform for gathering data.

“The fantastic thing about this vessel is it’s going from Bellingham to Skagway and back every week,” he said. “That’s a 1,600-kilometer run. Nowhere in the world is there a ferry system that’s outfitted with CO2 sensors that’s running that scale of a transit. This is really exciting.”

Evans said they expect to see seasonal changes in carbon dioxide, related to temperature; changes related to freshwater sources, such as glacier melt and stream outfalls; and changes connected to areas of large development.

“So, it’ll be a mosaic of different signals we’ll be seeing along the transit, and really fun to analyze from my standpoint,” he said.

Evans hopes the study can continue at least five years, but he’d really prefer it to last closer to a decade.

“ The challenge is really first understanding what the natural variability looks like in this data-poor region, and then making measurements long enough that we can tease out the long-term ocean acidification trend, which is this gradual increase through time,” he said “It’s really hard to see with just one or two years of data.”

Evans said the data will help fisheries management, especially oyster farmers. In Ketchikan, for example, a small, local study has given area oyster farmers a better idea of when to put animals into the water.

“We’ve been able to define a seasonal window of opportune growth conditions,” he said. “That’ sort of starts around March or April, and ends about now.”

Crab, also, are affected by ocean acidification. Evans said it’s not clear yet how much it affects other fisheries.

“We’re still trying to work out what the links are and who exactly the winners and losers are going to be,” he said “It’s really clear that shellfish are on the losing side.”

The monitoring equipment will run continuously and automatically, so nobody needs to be there watching it. Evans said they do plan on one or two ride-alongs per year to make sure everything is working correctly.

The data will be available daily, though, through an antenna on the bow. It will upload automatically to a website, available through the Alaska Ocean Acidification Network’s site. Evans said they’re designing it so that non-scientists can understand the data.

Christy Harrington is an environmental specialist with the Alaska Marine Highway System. She said ferry system officials were happy to work with the science team.

“It’ll be the biggest survey taking place in North America, from Bellingham to Skagway,” she said. “And the route that the ferry takes is very close to shore compared to other units on board other vessels. It will give them a lot more data that they can use. We’re just very excited to be able to provide the resource for the oceanographic equipment to be on board.”

Evans said the study wouldn’t be possible without partners like the ferry system.

He also mentioned the Canada-based Tula Foundation, the Alaska Ocean Observing System, Alaska Coastal Rainforest Association, University of Alaska Southeast and NOAA.

“One of my colleagues from NOAA, who is sort of the brains behind this equipment, Geoff Lebon, we wouldn’t be able to do this without their support,” he said.

All those partners eagerly await the first data. The Columbia is currently scheduled to resume its regular run in late October.

You can learn more about the ferry study here: http://www.aoos.org/alaska-ocean-acidification-network/ferry/