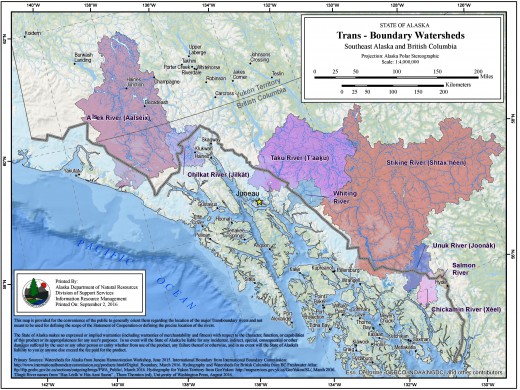

Eight transboundary watersheds feed Southeast Alaska rivers. A new agreement with British Columbia aims to protect them from mining pollution. Critics say it doesn’t do the job. (Map by Alaska Department of Natural Resources.)

Alaska and British Columbia officials signed a statement of cooperation Thursday aimed at protecting rivers that flow through the province and the state. But transboundary mine critics say it’s not strong enough.

The document is the result of about a year of talks following citizen warnings about B.C. mines and mining projects near the border.

Local and tribal governments, as well as fishing and environmental groups, said such mines could release pollution that would damage Alaska fisheries and traditional food-gathering.

British Columbia Mines Minster Bill Bennett said the agreement will give the state more input into the province’s environmental-assessment and permitting process.

He said the agreement will establish a technical committee — of experts, not politicians — to set up new water-monitoring systems.

British Columbia Mines Minster Bill Bennett signs a document on Thursday that promises cooperation on monitoring and protecting water quality. (Photo courtesy B.B. Ministry of Energy and Mines)

“We need baseline information so that we know whether there’s going to be or will be impact in the future from mining operations. We need these folks to figure out how we’re going to pay for it and who’s going to do it,” he said.

Alaska Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott, who has led the state’s effort on the issue, called the terms “another step in Alaska’s commitment to open and transparent collaboration.”

“It creates a technical working group to allow us to essentially put our hands on the power levers of the British Columbia government in its entire regulatory process of permitting mines,” he said.

The agreement was drawn up with feedback from mining, government, fisheries, community and environmental groups, as well as state and provincial officials.

Bennett said his ministry also reached out to First Nations members living in affected areas. He said similar outreach happened in Alaska.

“So I think on both sides of the border, we’re quite proud of the fact that this is not something that the two governments are imposing. This is something that, I think, has developed from the grass roots,” he said.

Some people disagree.

The Tlingit-Haida Central Council’s Rob Sanderson Jr. talks about transboundary mining March 9, 2016, in Juneau. (Photo by Ed Schoenfeld/CoastAlaska News)

Ketchikan’s Rob Sanderson Jr. works with the United Tribal Transboundary Mining Work Group. He said tribal governments on both sides of the border should be co-signers of the agreement. He also said it doesn’t address their most fundamental concerns.

“It’s not our business to issue permits to mining companies. Our business, in my opinion, is to maintain our culture for all future generations. This agreement does not do that,” he said.

Sanderson and other mine critics said the statement of cooperation, part of a larger memorandum of understanding, has little power to make significant mine-safety improvements.

They want the state to continue pursuing involvement of the International Joint Commission. That’s a U.S.-Canada panel handling cross-border water disputes.

“This memorandum of agreement throws a wrench into that. It’s because when you’re looking at it from the outside, they’re saying, ‘Well, probably, maybe we don’t need it. The state has a memorandum with the British Columbian government, so why go there?’ ” he asked.

Lt. Gov. Mallott says the statement of cooperation will not interfere with the state’s pursuit of joint commission action.

“We view this as a multi-track process, of which the SOC is but one,” he said.

The Southeast Alaska Conservation Council’s Guy Archibald said the document is much improved from earlier versions.

But in an email, he said some of its wording, such as the definition of “significant degradation,” is not strong enough.

Chris Zimmer of Rivers Without Borders was also critical. He said the agreement’s terms seem to answer British Columbia’s concerns more than those from Southeast Alaskans.

Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott signs a statement of cooperation with British Columbia Thursday. It targets protecting transboundary rivers. (Photo courtesy Office of the Governor)

B.C. mining companies and regulators said the existing process already safeguards transboundary rivers.

That’s a position taken by Alaska officials in past years, before citizen concerns led to talks that resulted in this agreement.

Only one mine – Red Chris – is up and running in the transboundary area. A second – Brucejack – is under construction. A third – Tulsequah Chief – is closed and needs clean-up.

But Bennett said another handful of exploration projects are far from development, due to technical and economic challenges.

“So, I don’t think you’re ever going to see a sudden emergence of a half-a-dozen new mines or something in northwestern British Columbia. But you will see other projects come along in the next 2, 3, 4 or 5 years,” he said.

Critics said even if it’s just one mine, it still threatens the environment and livelihoods in Southeast Alaska.