Karen Petersen and Mike Carney talk outside the Ketchikan International Airport’s new biomass boiler building. The pellet silo on the right holds up to 30 tons. (Photo by Leila Kheiry)

Ketchikan International Airport is just a few weeks away from switching its heat source to a high-efficiency biomass boiler system.

I rode over to Gravina Island with Karen Petersen. She was in town for a quick visit from Prince of Wales Island specifically to see the airport’s new biomass boiler.

“I work for the University of Alaska Cooperative Extension service, and chair the Alaska Wood Energy Development Task Group,” she said.

That group of about 20 evaluates applications from public agencies statewide for grants related to biomass heating systems.

The Ketchikan Gateway Borough was one of those applicants, and four years ago, its grant was approved. The borough used the funds for a feasibility study, and then successfully applied for a federal Woody BUG.

The Ketchikan Gateway Borough was one of those applicants, and four years ago, its grant was approved. The borough used the funds for a feasibility study, and then successfully applied for a federal Woody BUG.

“WoodyBUG: A Woody Biomass Utilization Grant, right? And now they are constructing and installing this wood heat system, and it’s really cool,” she said.

That grant, along with much larger state grants paid for the biomass boiler project, which also includes an oil-fired backup boiler, a building to house them both, and a silo that holds about 30 tons of pellets at a time.

After paying the toll for our short ferry ride to Gravina Island, where Ketchikan’s airport is located, we meet up with Airport Manager Mike Carney.

He takes us to a new green-sided building that houses the boiler, which is pretty small, considering that it will heat the entire airport. But, as Petersen explains in the elevator on our way over, some of the problems other facilities have had with their biomass boilers are because the boilers are too big.

“The problem that engineers have is if a little one is good, a big one is better, but that doesn’t hold true for biomass boilers that work efficiently when they’re working at full speed,” she said. “It’s better to put in a small one that works at 100 percent and then supplement it.”

A small boiler running at full capacity is more efficient, because it’s running constantly.

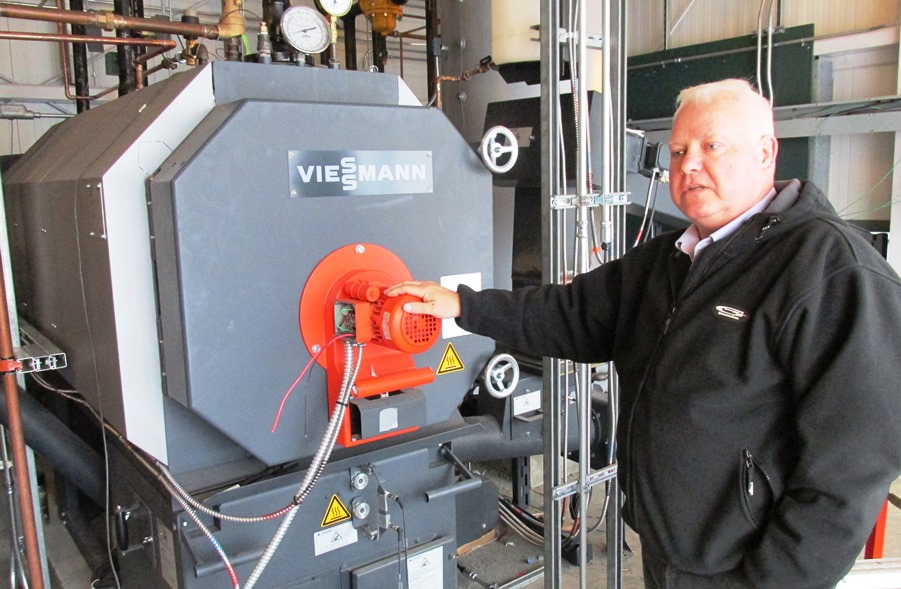

Airport Manager Mike Carney stands next to the Ketchikan International Airport’s new biomass wood-pellet boiler. (Photo by Leila Kheiry)

Starting and stopping is where efficiency is lost.

And to maximize efficiency even more, there’s a 1,200-gallon thermal storage tank.

“So, the boiler is going to heat the water in the thermal storage and that’s what its job is, is to keep this tank hot all the time,” she said. “What that means is, it’s going to keep this – set at 175-180 degrees – it’s going to keep this (hot) constantly, and then the heat from the building is going to draw off this thermal storage through heat exchanges.”

Carney said that even with the extremely low current price of oil, he expects the new boiler will save the borough in fuel costs. Locally owned Tongass Forest Enterprises has the contract to deliver the airport’s pellets at a cost of about $300 a ton.

They’ve budgeted for 100 tons a year, which adds up to about $30,000.

Carney said that last year, the airport spend about $42,000 on fuel oil. That’s with low prices and a mild winter; they have in the past spent up to $70,000.

And, Carney said, as demand for wood pellets grows, the price of that renewable fuel should drop even more. Ketchikan High School is next in line to get biomass boilers, and will need about 11 times the volume of pellets as the airport.

Petersen said she’d like to see more people using pellet boilers for home heating, as well. She uses it herself, and said it works great.

“It takes a shifting in your attitude if you want to go ahead and heat with wood, but I tell you what: I’d rather know where my fuel is coming from, and I can see my fuel source out my window,” she said.

Part of the problem is that wood stoves of the past weren’t efficient and created a lot of smoke, leading to a bad reputation. Wood pellet boilers are much more efficient now. Carney said he’s observed other wood-pellet boilers in action.

“There was no smoke,” he said. “You can stick your hand into the stack, pull it out and not smell any smoke or see any smoke.”

To improve the image of biomass to visitors, the building that houses the airport’s new boiler will serve as an ambassador of sorts, with windows so people can see the boiler at work.

“The idea there is, people will be able to look in here,” Carney said. “This’ll be all painted. There will be a storyboard outside that tells how this works so the traveling public will be able to see it.”

The entire project cost was about $950,000, all paid for through grants. Carney said the Alaska Energy Authority provided the bulk, and the rest was a legislative grant that incorporated the federal WoodyBUG.

Once the new boiler is fired up and pumping out heat, Carney said he plans to host a ribbon-cutting celebration, and invite everyone who has helped move the project along.