History can come in all shapes and sizes. University of Washington PhD student Ross Coen was in Ketchikan in mid-November to give a presentation on the history of the canned salmon industry in Alaska, and to research a subject he’s passionate about, salmon can labels.

Audio PlayerRoss Coen admits that he’s a “nerd” when it comes to his interest in salmon can labels. Just like someone might collect baseball cards, there are those who collect labels from fish packers. Coen was at the museum in Ketchikan recently to observe photos, documents and other archival information about the canned salmon industry for his research. He also helped to document and catalog salmon labels in the museum’s collection.

Coen says the canned salmon industry was at its height in the early 1900’s. At that time, refrigeration wasn’t generally available and canning provided an easy way to transport food throughout the world. Coen says part of his fascination with fish packing labels is that they tell a history of time and place.

“Each label is a snapshot, a moment in time of history, that reflects the political circumstances, the cultural conditions and economic conditions that were going on at the time that these labels were produced and the salmon was marketed.”

Coen says fish packers often incorporated current events into label designs.

“For example, there’s a William Henry Seward label of canned salmon honoring the Secretary of State who purchased Alaska in 1867. There are labels related to World War 1, World War II. Labels that were exported to Great Britain might have an image of Queen Victoria. So each one of these labels has some direct link to the historical events at the time they were created.”

Coen says many of the labels are also works of art. He says most of the labels found in museums come from label collectors. He says they are often in pristine condition because they were never placed on a can.

“These labels were the ones that were maybe in an envelope in a file cabinet, never actually used on the market. They end up in the hands of collectors who then sell, trade or donate them to the museum.”

The Tongass Historical Museum’s collection includes many labels from Alaska but also from canneries in Washington State and other parts of the Pacific Northwest. Coen says some of the earliest canneries were in Southeast Alaska, including those in Metlakatla, Klawock and Ketchikan. The museum has labels from several of those canneries.

In viewing the labels, Coen says one that he found most interesting was a “family brand” packed by the Peratrovich family of Klawock in the late 1800’s. Coen describes the label.

“This is John Peratrovich, an immigrant from Croatia, with his Native wife and two children. The young boy he is holding in his lap is Roy, who I believe is the father of Frank and Roy Peratrovich who were Native leaders and very active in Native Civil Rights and the Alaska Native land claims movement is the 20th Century. So this label is really quite fascinating.”

“This is John Peratrovich, an immigrant from Croatia, with his Native wife and two children. The young boy he is holding in his lap is Roy, who I believe is the father of Frank and Roy Peratrovich who were Native leaders and very active in Native Civil Rights and the Alaska Native land claims movement is the 20th Century. So this label is really quite fascinating.”

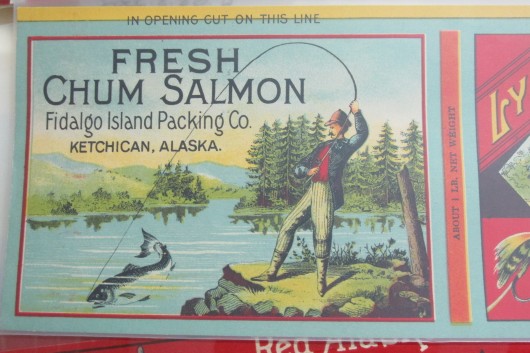

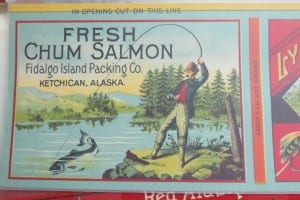

Another label Coen found fascinating was the Lynx Brand packed in Ketchikan in the late 1800’s or early 1900’s which features an image of a fisherman catching salmon in a stream with a fishing pole.

“Now of course that’s not how salmon were caught for the commercial packing industry, but this is an example of the packers trying to communicate a sense of nature to the consumer. If you’re a housewife in Des Moines, Iowa or something like that, you see this can on the shelf. Seeing this handsome, strapping fisherman catching your salmon conveys that sense of purity and wholesomeness and nature that the packers were trying to communicate.”

“Now of course that’s not how salmon were caught for the commercial packing industry, but this is an example of the packers trying to communicate a sense of nature to the consumer. If you’re a housewife in Des Moines, Iowa or something like that, you see this can on the shelf. Seeing this handsome, strapping fisherman catching your salmon conveys that sense of purity and wholesomeness and nature that the packers were trying to communicate.”

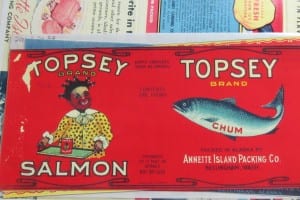

Coen says the primary market for Alaska salmon in the early 1900’s, especially pinks and chums, was the American South. He says some of that imagery is highly racialized with Civil War scenes and slaves picking cotton in the fields. He says while these labels were prominent around the turn of the century, racialized imagery faded away, especially given political change and the Civil Rights Movement.

The Tongass Historical Museum has more than 100 canned salmon labels in its collection and the images range from simple to ornate. The labels are kept in the museum’s archives, and made available to researchers, such as Coen. Some, however, may become part of a future museum display.