The Tulsequah Chief Mine is on the banks of its namesake river, which flows into the Taku River, which enters an ocean inlet about 25 miles northeast of Juneau. The brownish pools contain acidic water draining from the mine. (Photo by Joe Hitselberger/ADF&G)

Can British Columbia stop polluted water from leaking out of a long-closed mine upstream from Juneau? The issue came up last month when the Canadian province’s top mining official traveled to the Capital City.

The Tulsequah Chief hasn’t been open for more than 50 years. But, like many old mines, it’s leaking pollution.

For decades, rusty, acidic water has drained from an old tunnel into a nearby river.

“I was there. I took pictures of it and you can see it,” says British Columbia Minister of Mines Bill Bennett, who saw the Tulsequah Chief during his August visit to Southeast Alaska.

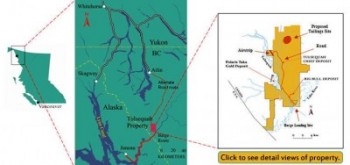

It’s on the Tulsequah River, a tributary of the Taku River. That salmon-rich waterway empties into an ocean inlet about 25 miles northeast of Juneau.

B.C. Minister of Mines Bill Bennett discusses the Tulsequah Chief Mine as Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott listens, Aug. 24 in Juneau. (Ed Schoenfeld/CoastAlaska News)

“It’s something that B.C. is responsible for and I think if … I was from here I’d be asking all kinds of questions about the Tulsequah Chief Mine situation as well,” he says.

Bennett promised to do something about it, but didn’t offer specifics.

Toronto-based Chieftain Metals, which owns and plans to develop the mine, did not respond to an interview request. But the company’s been in touch with the mines ministry.

Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott accompanied Bennett during much of his Alaska tour.

“While he was here, he informed me that he had contacted the CEO of the company and had talked to him about the continuing discharge and the need for water treatment or some mitigation,” he says.

Mallott says he hasn’t yet heard any details, and will follow up. British Columbia’s Mines Ministry offered no further information.

While Bennett promised to do something about the mine drainage, he downplayed its threat to the environment.

The Tulsequah Chief Mine is northeast of Juneau, just across the border in British Columbia. (Map by Chieftain Metals.)

“You’ve got a tremendous amount of data that shows that there isn’t any impact on water from what’s happening at Tulsequah Chief. There isn’t any impact on the Tulsequah River and certainly no impact that has been noted in all the testing that’s done in the Taku River,” he says.

“To say this is not harmful, you cannot say that,” says Chris Zimmer, Alaska campaign director for Rivers without Borders, which is highly critical of transboundary mine development.

He says the studies Bennett cites were not at all comprehensive.

“It didn’t look at juvenile salmon. It didn’t look at the sediment. It didn’t answer the question, where is the material that’s coming out of the mine ending up?” he says.

That rusty, acidic outflow is caused when water runs past tunnel walls and floors and waste rock leftover from mining. The Tulsequah Chief has no tailings dam.

Chieftain Metals addressed the problem in a promotional video it posted on YouTube in May of 2013.

“We’re building a water-treatment plant that will treat that acidic water and turn it into very clean water that will be released into the river,” Chief Operating Officer Keith Boyle says.

The plant went into operation, but only for awhile.

Chieftain said it cost too much to run without revenue from full-scale mining. But the company doesn’t have all the permits and investments needed to do that.

“So relying on the mining company to operate the mine and the clean it up seems like a nonstarter,” says Rivers without Borders’ Chris Zimmer.

He says the province could step in and fill the mine tunnels generating most of the polluted water.

“So the question comes down to, are you going to run that plant forever at $4 million a year? Or are you going to spend a lot of money right now and go shut down and reclaim the site?” he says.

Reclamation is not a step British Columbia is likely to take.

Chieftain has an environmental permit needed to build the mine. Bennett says recent plans to barge ore, rather than ship it via a new British Columbia road, mean the permit needs to be amended.

That will require consultation with the Taku River Tlingit First Nation. The mine is in their traditional territory and they’ve filed a lawsuit to block development.