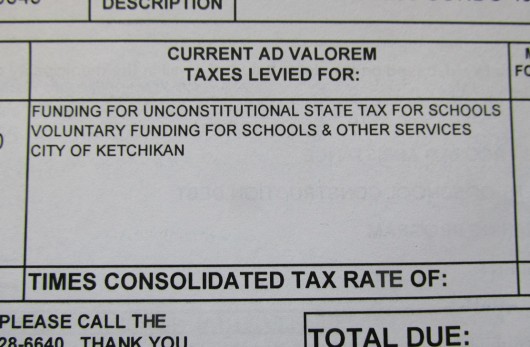

A 2015 property tax bill from the Ketchikan Gateway Borough includes a break-out of how much a homeowner pays toward the state’s required local contribution for public education. (Photo by Leila Kheiry)

A flurry of briefs was filed by the June 30th deadline with the Alaska Supreme Court in the Ketchikan Gateway Borough’s ongoing lawsuit challenging the State of Alaska’s requirement that local governments earmark a certain amount of property taxes for public education.

“I’ll go out on a limb and say I’m absolutely confident that we are correct in this matter,” says Borough Manager Dan Bockhorst.

He knows the borough has a good case. They won the first round, after all, when Superior Court Judge William Carey ruled in January that the state’s required local contribution for schools violates the Alaska Constitution.

The question is: Will the Alaska Supreme Court uphold Carey’s decision?

State attorneys didn’t waste any time filing an appeal with the high court, and Carey’s decision was put on hold pending that appeal.

Borough officials also filed an appeal because, while winning the main point, they didn’t get everything they wanted. Judge Carey ruled against the borough’s request for a refund of the previous year’s required local contribution – about $4 million.

The most recent filings with the high court allowed each side to argue why the justices should rule against the other side. The borough relied on a prior case, State v Alex, which in the 1980s, challenged a required tax, which went directly from commercial fishermen to regional aquaculture associations.

In that case, the Supreme Court ruled that the tax violates the Constitution’s prohibition against dedicated funds.

The borough’s brief focuses on similarities between Alex and the current case.

“It absolutely hits it, every point,” Bockhorst says.

Borough Attorney Scott Brandt-Erichsen adds: “One of the lynchpins of the arguments that the state makes is that, if the money doesn’t hit the state treasury, there can be no dedication and you don’t have to appropriate the money. But in the Alex case, the money never hit the state treasury.”

He explains that the Constitution stipulates that public funds can’t be dedicated, or earmarked, by the state – revenue has to be appropriated on an annual basis by the Legislature.

The state counters that the required local contribution isn’t state revenue, and that the statute only requires local funding – not necessarily a local tax. But Bockhorst says the only realistic way a local government can raise the mandated millions of dollars every year is through taxes, and that those local taxes are a back-door way for the state to fund schools.

“The state is able to fulfill its Constitutional obligation to adequately fund schools by forcing us to levy what amounts to state taxes,” he says. “We get the blame and they get the benefit.”

The borough didn’t win the refund issue because Judge Carey ruled the state wasn’t enriched by the required local contribution. The Legislature can choose to reduce or increase school funding each year, and the mandatory local contribution doesn’t necessarily factor in to that process.

The borough, though, contends that the state is, indeed, enriched.

“If we’re compelled by the Legislature to spend a chunk of money in furtherance of their responsibility, then that money is being spent for their benefit, whether they’re required to fully fund or not,” Brandt-Erichsen says.

With this latest set of briefs filed with the Alaska Supreme Court, each side now has until July 28 to respond in writing. After that, the next important date is Sept. 16. That’s when oral arguments are scheduled with the Supreme Court in Anchorage.

“And the Supreme Court has signaled in the past that they plan to rule promptly,” Bockhorst says.

An exact timeline for a decision is not known, but ideally a ruling would be announced prior to the next legislative session. That way, everyone would know before lawmakers convene in Juneau whether or not the state needs a whole new education funding system.