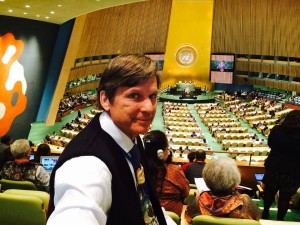

Tlingit-Haida Central Council’s Will Micklin attends the United Nation’s World Conference on Indigenous Peoples Sept. 22, 2014.. (Photo courtesy Indianz.com)

Alaska’s largest tribal government is part of an international effort to boost Native influence in the United Nations.

The Juneau-based Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska wants a larger forum to address its concerns.

The U.N. has focused attention on indigenous issues in recent years, such as returning artifacts to tribes and preventing violence against women.

Jacqueline Johnson-Pata is executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, as well as part of the central council’s leadership.

She told a recent tribal assembly that a more formal arrangement is needed.

“Tribes and governments, elected representatives of indigenous nations, should have a voice in the United Nations. We shouldn’t just go as an organization. But we should go as a representative government,” she says.

Central Council First Vice President Will Micklin agrees.

“We are a nation with longstanding international relations with other countries and have issues that cross boundaries,” he says.

Micklin is also CEO forfor the Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians, near San Diego, and executive director of the California Association of Tribal Governments. He’s a strong advocate of United Nations involvement.

“The only way to address these issues like climate change, like water resources, like fisheries, like the environmental impacts of extractive industries is to engage in the international arena,” he says.

The 30,000-member central council is part of a nationwide movement pursuing increased involvement in the United Nations. It’s been active for several years.

Micklin says the effort stems from the U.N.’s 2007 Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which also targets discrimination and human-rights violations.

“We envision and have proposed to the secretary general all rights and privileges for indigenous governments the same as a member state,” he says.

“We envision and have proposed to the secretary general all rights and privileges for indigenous governments the same as a member state,” he says.

That would put tribal members on committees and allow them to submit reports.

“The only distinction is we would not be able to vote as a member state in the general assembly,” he says.

He says tribal governments have met with U.N. and federal officials, and they’ve found support.

Terry Sloan is director of the New Mexico-based group Southwest Native Cultures. The Navajo-Hopi, who already serves on United Nations committees, says more outreach is needed.

“What’s happening is that a lot of the tribes aren’t fully aware of this declaration, what it means and what it contains. So there is going to be some sort of an educational process throughout the country,” he says.

He also says many indigenous groups outside the U.S. aren’t aware of the effort. Many have faced violence when attempting any form of organization.

Sloan just returned from a meeting following up on the U.N.’s World Conference on Indigenous Peoples.

He says there was no consensus and years could go by before formal recognition happens. But he remains optimistic.

“When and if and how long it takes to get the implementation process through, we will see great gains for the Native Americans of the United States,” he says.

Sloan says despite differences, the Obama administration is very supportive of the U.N. effort.

He says the U.S. could become a model for other countries’ tribal government roles in the international organization.