Water disinfection was the hot topic in Ketchikan this week, with several presentations, two from a water treatment specialist who works with national consumer advocate Erin Brokovich; and one by a water treatment consultant who is member of the Alaska Water and Wastewater Advisory Board.

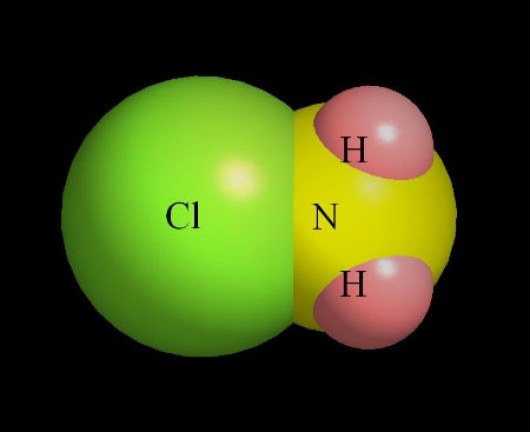

The controversy is over the City of Ketchikan’s plan to start disinfecting its public water system with monochloramine – a combination of chlorine and ammonia – in order to bring the city’s water into compliance with federal regulations limiting certain byproducts.

About 250 people showed up at Ketchikan’s Ted Ferry Civic Center for Bob Bowcock’s presentation about why chloramine is not a good idea. Bowcock works with Erin Brokovich, and gives similar presentations all over the United States. He argues that merely meeting Environmental Protection Agency regulations doesn’t mean the water is safe, or free from dangerous byproducts.

“There are thousands of studies that tell you how bad chloramines are, but the EPA hasn’t had time to look at them, so in the next generation or two they might get around to it and then, there will be regulated byproducts,” he said. “But until then they’ll tell you chloramines are safe because none of the byproducts are regulated. Does this mean that Ketchikan consumers should be forced to suffer from the medical conditions and property damage while we wait? I say no.”

Potential medical conditions Bowcock mentioned include skin irritation – sometimes severe – from bathing in chloramine-treated water, respiratory reactions from breathing the evaporated chemical and more. Property damage includes rubber seals for plumbing that have been shown to disintegrate more quickly when exposed to chloramine-treated water.

Bowcock also warned about the potential for large fish kills if a lot of chloraminated water leaks into a creek, through a water main break, for example.

During his nearly two-hour-long public presentation and his shorter presentation to the Ketchikan City Council, Bowcock recommended that the city consider alternatives. The byproducts that the city is trying to reduce form when organic material – leaves, tree bark, etc. – come in contact with the chemical used to clean the water.

So, Bowcock said the best way to reduce those byproducts is to remove the organic material. And he recommends a granular activated carbon contact vessel system.

“What a contact vessel is, it’s not a filter,” he said. “The water gets in there like a washing machine and moves around with the carbon.”

And the carbon attracts bacteria and other organic compounds, thus removing them from the water. In a separate interview with KRBD, Bowcock estimated that the cost of such a system for Ketchikan’s water needs could be $4 to $8 million.

He also suggested an aeration system – basically a pump that floats in the storage tank and sends air through the water. Such a system could help reduce the byproducts, which he said dissipate in air.

Mike Pollen is a water and wastewater consultant based in Fairbanks. He serves on the state water wastewater advisory board and was in Ketchikan to conduct training for some of the city’s water treatment employees. He spoke during the Council meeting, and disagreed with much of what Bowcock presented, calling the information “subfactual.”

Pollen said chloramination has been used since 1917, and is used in many communities, including Denver, Colorado. He said about 20 percent of the United States uses chloramine-treated water.

“That represents something in excess of 65 million people. The vast majority of those people are not dropping dead on the streets from chloramines, I’m here to tell you,” Pollen said. “The bottom line is the EPA has continued along with AWWA – American WaterWorks Association – to recommend this particular technology as an alternative for a secondary disinfectant.”

Pollen described numerous water treatment options used in Alaska – many of which are very expensive. He notes that the one option that has failed miserably in the state is granular activated carbon.

“GAC does not work here for a couple of reasons, one is the characteristics of the type of organic matter that’s in our surface water,” he said. “I don’t know what it is, maybe it’s some kind of organic goo, but it doesn’t take well to activated carbon.”

Pollen also said that the aeration system Bowcock mentioned won’t take care of Ketchikan’s byproducts problem. It will remove one kind of byproduct, but is not proven to remove or reduce haloacetic acids.

Bowcock came to Ketchikan at the request of a citizen group called United Citizens for Better Water. That group is collecting signatures for a ballot initiative that would prohibit the city from using chloramine as a water disinfectant. But the city was going to turn on the new system this spring, and the initiative process could take a few months.

Amanda Mitchell, who helped start the group, asked the Ketchikan City Council to delay the implementation of the new water system until after the petition process was complete. The Council agreed to wait at least until after its March 20th regular meeting, when the issue will be on the agenda.

Ketchikan’s new water treatment plant has been developed over the past 10 years. There were delays in starting the new system on because of contractor issues and then a long wait for the state to issue an operating permit.

Related links:

http://water.epa.gov/lawsregs/rulesregs/sdwa/mdbp/chloramines_index.cfm

http://www.city.ketchikan.ak.us/public_utilities/waterconv.html

A video from Bowcock’s presentation, posted on YouTube by an audience member:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=niQCgR4PJAQ

Previous news stories:

https://www.krbd.org/2014/03/03/anti-chloramine-group-starts-ballot-initiative-process/

https://www.krbd.org/2014/02/05/group-opposes-citys-plan-for-chloramine-disinfection/