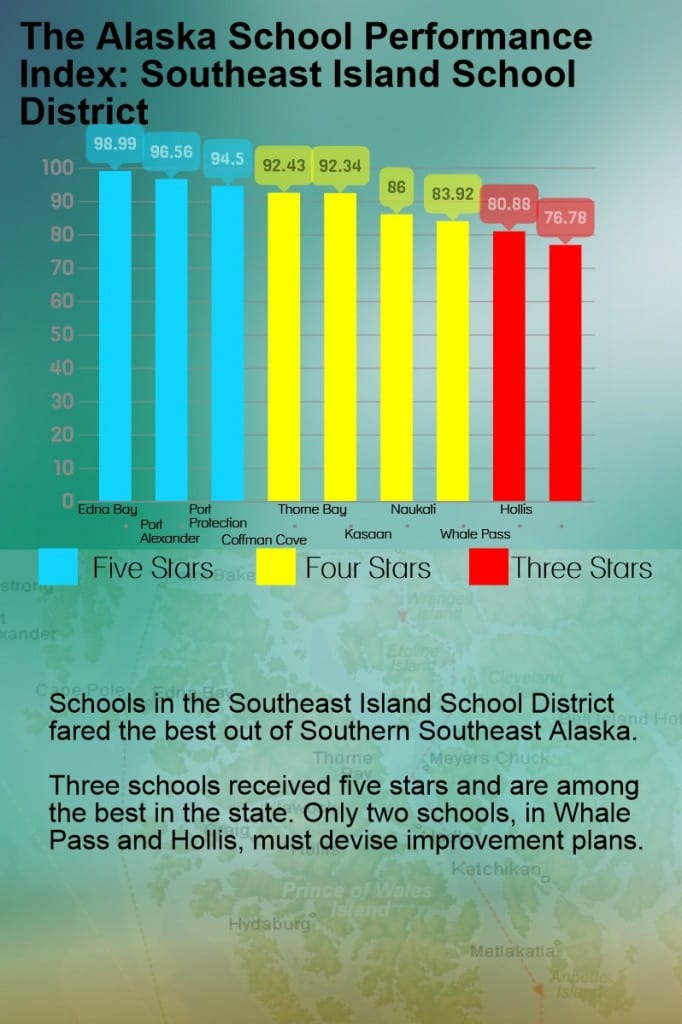

Area schools are doing… OK. Most of them fall somewhere in the middle or better-than-average range of the state’s new school evaluation system. Some schools received the top rating for this year, but a few are at the bottom.

“Those schools aren’t being crushed by some state-imposed consequences,” says Eric Fry, a spokesman for the Alaska Department of Early Education and Development. “But we couldn’t, we weren’t allowed, to create a new system for them.”

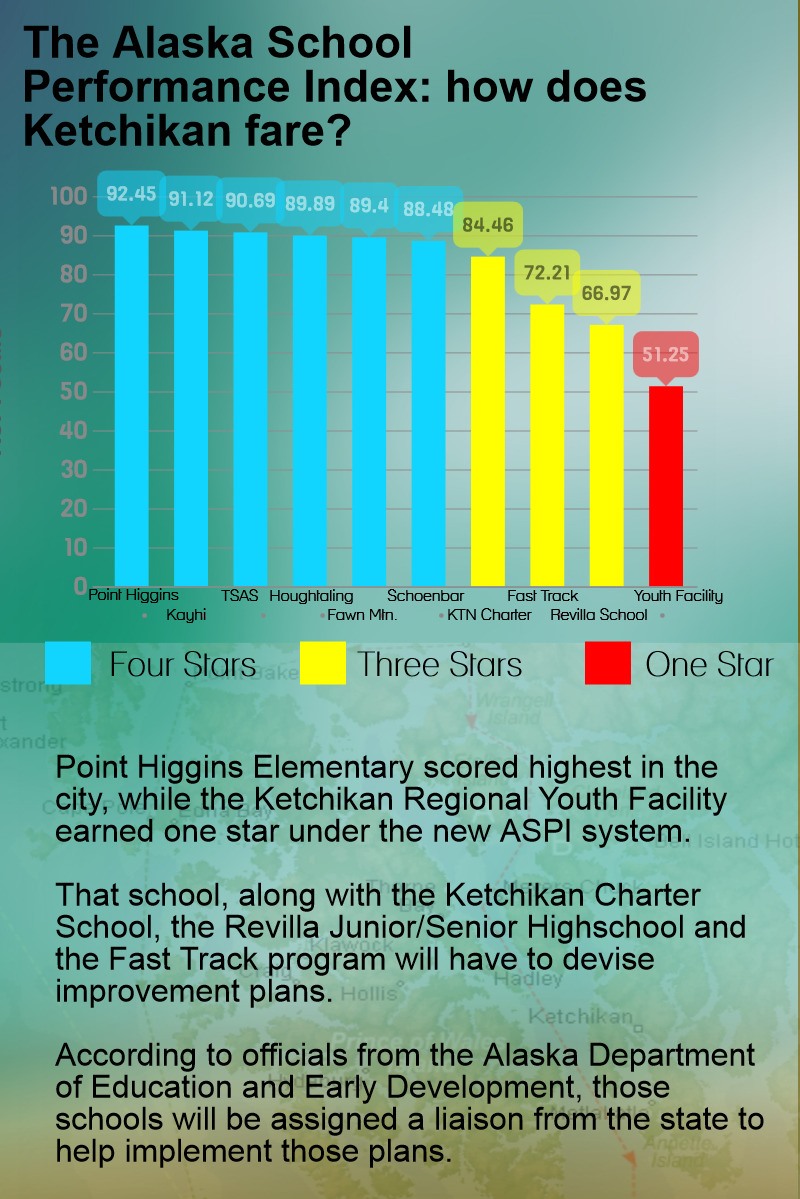

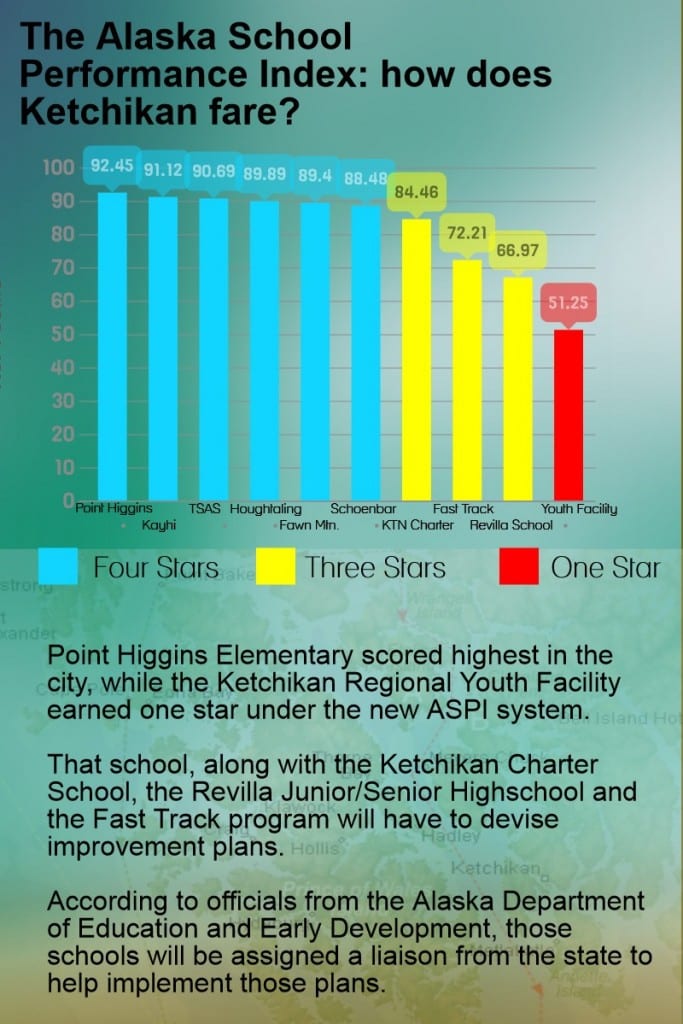

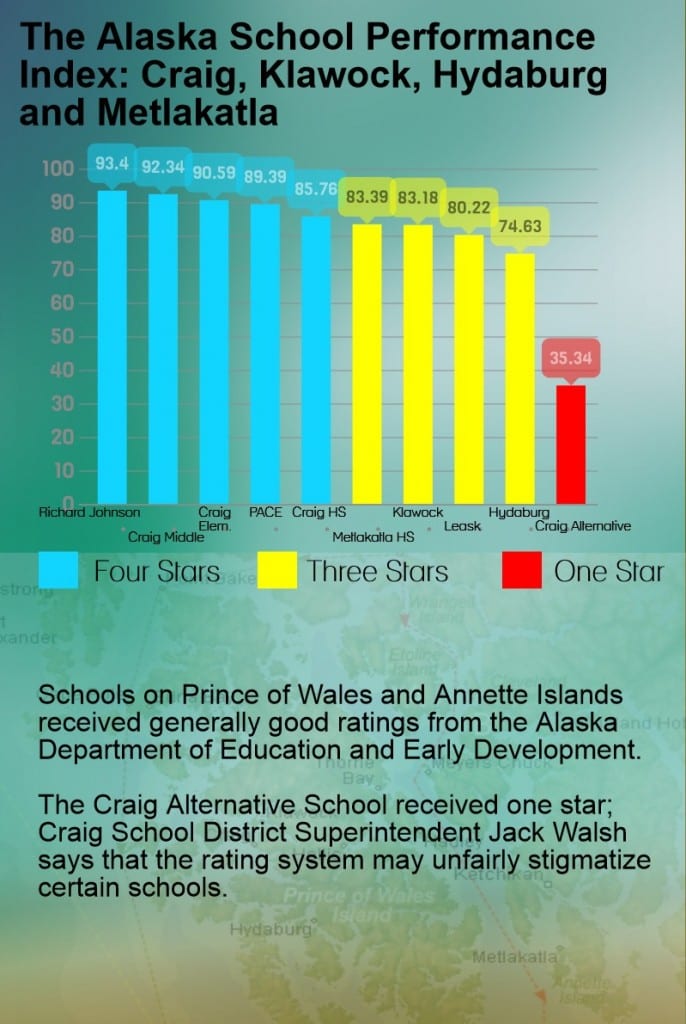

Fry says that some alternative schools, like the Ketchikan Regional Youth Facility or the Craig Alternative School that received one out of a possible five stars under the new system, were bound to receive the ratings they did because of the nature of their school population.

The spokesman told KRBD that ASPI is still constrained by federal regulations under the No Child Left Behind act, despite the state’s effort to build a different system. DEED would like to have a separate evaluation program for alternative schools, which take in students who don’t fit in with traditional institutions, but the federal government allows only one rating system for all schools.

Despite that, Fry says local populations should understand that an alternative school receiving one star doesn’t necessarily reflect on the quality of the institution.

“If the public is educated about the nature of the school, the local public should not look down on those schools, which deal with some of the most struggling students,” he says.

ASPI differs from No Child Left Behind in that it uses a variety of factors to grade schools on a scale, rather than on a simple pass/fail basis. Taking into account graduation and attendance rates, test scores and the rate of improvement, schools are given a rating from 0 – 100. That number can then be translated into one to five stars, with five as the best.

Those with three stars or fewer are required to devise an improvement plan. A number of schools in the area fall into that category, for example: Metlakatla High School, Ketchikan Charter School and Klawock City School.

Craig School District Superintendent Jack Walsh says a system that rates schools in this way is unwise. In the instance of the Craig Alternative School, which received one star, he believes it will unfairly stigmatize the institution.

“Many of these kids might have been dropouts, and now we’re asking them to go to a school with a one-star rating,” Walsh says. “And it’s just like hotels or anything else, rarely do people want to go search out places that have one star and think it’s the best place to be.”

Schools with three or fewer stars under the new system will be assigned a liaison from the state to monitor improvement. In some cases, a “coach” hired as a contractor by the state will be sent to schools with lower ratings. Those coaches work with school administrators and teachers for a week, devising strategies to improve performance.

DEED Deputy Commissioner Les Morse notes that the new system isn’t devised to punish schools with lower ratings. The objective is to locate and diagnose problems, and then devise a specific plan for individual schools that need support.

“Rather than having a blanket set of consequences that may or may not work, the consequences actually apply to where the weaknesses are after the problem is truly diagnosed,” Morse says. “It’s not that we’ve let go of consequences, we just realized that there isn’t a one-sized fits all approach.”

The new ratings system was devised because Alaska’s application for exemption from the No Child Left Behind Act was approved.