A few years ago, a set of 20,000-year-old human footprints in a dry lakebed in New Mexico set scientists reeling. Those fossilized footprints, originally discovered in 2009, called into question what we thought we knew about when people first showed up in North America. Archaeologists thousands of miles away in Alaska felt the scientific impact especially strongly.

A recent paper published in the journal Nature attempts to set a new timeframe of when the first humans might have appeared along the coast of Southeast Alaska, using cave remains and animal fossils from the region.

But it’s just one piece of a much bigger puzzle.

The Nature article caught Nick Schmuck’s attention. He’s an archaeologist with the Alaska Department of Natural Resources. He said how and when people showed up in Alaska and the Americas is a debate that may never be settled in the scientific community.

“It doesn’t take long getting into the literature on this topic to realize that this is really a heated debate,” Schmuck said. “You’ve got folks who are diehards for one idea. You can think about it as paradigms, you know, we all think about a topic in a certain way for a while.”

According to Schmuck, there are many theories in this debate but currently, the most commonly held belief is in “Coastal Migration Theory”.

Remember learning about the Bering Land Bridge in middle school? That’s part of the Coastal Migration Theory, which basically goes that after the last Ice Age, early humans migrating from Asia crossed a stretch of land, the Bering Land Bridge, between Russia and Alaska in search of food. Then they traveled, either by foot or by boat, down along the coast of Alaska, and into the rest of the Americas.

“These people coming into the Americas – doesn’t matter how far back we go – they’re just as capable as you and I. So, they can figure out how to use boats. They were no strangers to rivers and things like that, so, why not the coast?” Asked Schmuck. For his own part, Schmuck is a bit of a pluralist. He believes this is one of many potential routes early humans tread.

The recent Nature article, “New age constraints for human entry into the Americas on the north Pacific coast” by Martina Steffen, attempts to tighten the parameters of the coastal migration debate. The paper looks at gaps in dates of animal fossils and archaeological sites, including 18 caves and sites in Southeast Alaska.

During the iciest part of the last Ice Age, a massive ice sheet advanced across the western part of the continent and over Prince of Wales Island, the largest island in Southeast. All of that now dry land, buried under thousands of tons of ice. Archaeologists believe that at its peak — known as the “glacial maximum” — about 18,000 years ago, that giant wall of ice would have blocked off any land routes down the coastline. Think of it like a gate that closed for over 1000 years.

So, the commonly held belief is that people showed up after that, as the glaciers melted from the outside in, revealing land and food to eat.

For Schmuck, it isn’t just the fossil record that supports this post-glacial theory, it’s the spoken record of the descendants of these first people.

“They sound like people coming to an early post-glacial Southeast Alaska,” Schmuck said, describing oral histories. “They talk about coming to a land that’s just a narrow strip of land between the ice and the sea. Like, holy cow! That’s what Southeast Alaska would have been before the trees came in.”

“I think the important thing to remember is that we know that we have been here for at least 12,000 years. We know that from DNA science,” said Kaaháni Rosita Worl, a Lingit anthropologist and president of the Sealaska Heritage Institute.

Worl is a descendant of those first people. “To me, it affirms our oral traditions that say we’ve been here since time immemorial,” she said.

If the carbon dating was done correctly, and most archaeologists now agree it was, the New Mexico footprints are much older than the signs of human life found in Southeast Alaska. That means the footprints were from someone who was in North America before those giant ice sheets sealed the land shut, which, in turn, means that either the humans that left the New Mexico footprints didn’t cross the Bering land bridge at all or people were here much earlier than Western scientists had thought.

“There had to be another route,” said Worl. “And the coastal route – it opens up and you have resources available that people could live on.”

The footprints changed everything, according to Bryn Letham, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. And of course, he says, there were skeptics. Some made a plausible argument that the carbon-dating was wrong. But as time went on, that didn’t seem to be the case. The White Sands team kept testing the fossils and every time got the same result: that footprint was from someone 21,000-23,000 years ago.

In a 2024 article for PaleoAmerica, Letham wrote that it was breathtaking, but it also raised an existential question for him and his colleagues: “What have we been spending our careers doing?”

Had they been searching in the wrong places? The wrong times?

The footprints in New Mexico started a race among those studying the Pacific Northwest coast. Most of the geologists and archaeologists are united by a common goal — to find the oldest sites of human occupation.

Currently, the earliest signs of life in Southeast Alaska is Shuká Káa – a human skeleton and set of tools from about 10,300 years ago in a cave on Prince of Wales Island.

It’s possible archaeologists just haven’t found older evidence yet, because of the challenges of searching in the forest-covered region.

“I mean, you’ve been in the Tongass, it’s big trees. It’s hard to see very far ahead of you and it’s hard to imagine what the landscape looked like,” said Nick Schmuck, adding though that the technology is improving. Specifically, a method called LiDAR that can map the earth’s topography using pulsed lasers.

“It takes all the trees off and gives you a new map based on the surface. All of the sudden, beach terraces pop out like you wouldn’t believe. And you can just look at the image and say, ‘Oh, there’s an ancient shoreline right here.’ And you can hike right to it. And boom, there’s your 10,000 year old beach with a 10,000 year old site on it.”

Another factor in Southeast Alaska is what one scientist refers to as almost a tectonic seesaw effect. During that glacial maximum, the massive ice sheet that covered the mainland was so heavy that it literally pushed the land down. That caused the outlying islands and land masses further off the mainland to rise up above sea level, like a seesaw. What this means for Southeast Alaska is that a lot of the oldest evidence of humans is probably either at the top of a mountain or the bottom of the ocean — which is where Kelly Monteleone comes in.

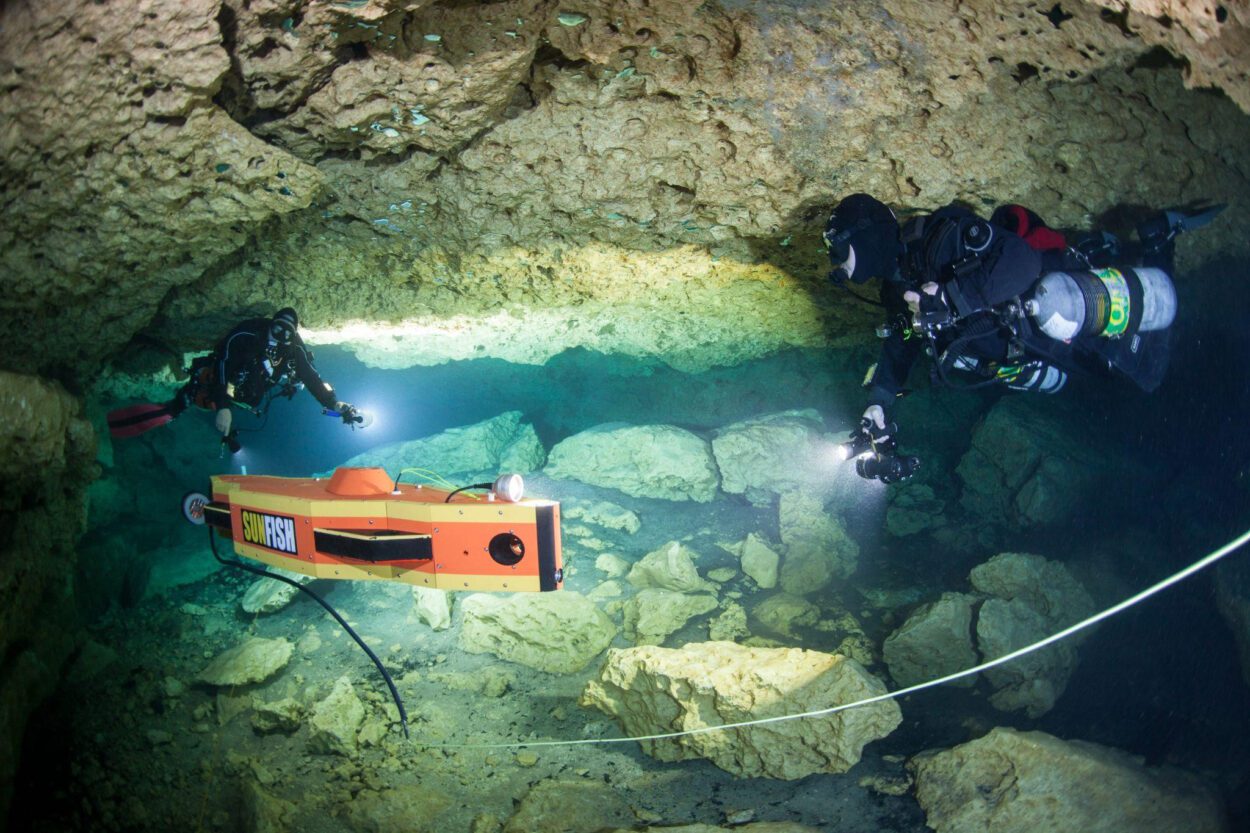

“There’s this huge, vast area that we haven’t explored yet. And so there’s so much we can find,” Monteleone explained. She’s an underwater archaeologist with Sealaska Heritage Institute. Monetleone said her profession is pretty much the same thing as a regular archaeologist, plus some extra work.

“Nothing changes between the terrestrial answer and the underwater answer, we just have a much more complicated step every step of the way,” she laughed.

What Monetleone and her team find on the seafloor changes the “when” of coastal migration.

“I see myself as having the resources to help answer the questions of the Indigenous people of Southeast Alaska. So I have the skills as an underwater archaeologist to go out and look in areas to help them learn about their past,” she said.

As Bryn Letham put it, the current people of the coastal First Nations are the descendants of those first post-glacial humans.

Schmuck agreed, saying that in Southeast Alaska, “we’re talking about the ancestors of people who’ve been here for a really long time.”

He acknowledged that archaeology as a profession hasn’t always been a positive force in that regard. “We don’t want to get too abstract about the people in the past. We don’t want to get back into the old faults of archaeology, where we’re just looking at rocks and forgetting to think about people. These are people’s ancestors.”

Letham, Worl, Schmuck, and Monteleone all point out that the Indigenous peoples along the Northwest Coast are strikingly diverse. There are so many languages and cultures in such a condensed area and they are so isolatedly different from each other that it seems like people would’ve had to have been here a lot longer than other parts of the Americas. In other words, it takes a lot of long, sustained time in one place for entire languages and cultures to develop. On the northwest Pacific coast, there are dozens in close proximity, each distinctly different from the next, which tells anthropologists that people got to Southeast Alaska after the last Ice Age and stayed, splintering off into tribes and isolate cultures over many thousands of uninterrupted years.

These origins are old — and not like black-and-white TV old or even musketballs and oil lamps old. More like the great and silent mists of time old.

“The concept of time at 12,000 years is not a concept that humans can usually digest,” said Moneteleone. “Time immemorial, the beginning of time. 12,000 years ago, 16,000, 20,000 years ago, those are all the beginning of time.”

And while the rest of the world chases after New Mexico’s footprints, Monteleone says that understanding the history of the people of the Northwest Coast is an archaeological field of study that is still in its infancy.

Get in touch with the author at jack@krbd.org.